A year or so after QST first began its International Amateur Radio department, amateurs were discussing linking amateur radio organizations around the world. In a speech at the second ARRL National Convention in late 1923, Maxim said he believed it was time for an international meeting to organize something he called a “World Amateur Radio League,” and asked members to submit their ideas for the ARRL board to consider.1 ARRL secretary and QST editor Kenneth Warner echoed the sentiment, declaring that “International Amateur Radio has arrived,” and, “we need an International Amateur Radio Relay League” which ARRL would play a part in organizing.2 The League had just completed a major restructuring, adopting a new constitution on 18 December 1923.3 After the war a new board of seventeen directors at large had been elected in a poll of the entire membership. While this had worked fine for a while, especially in getting things going again after the shutdown, it failed to provide regional representation. The organization had grown quite a bit in four years and it was time to fix this deficiency. The new constitution provided for one director from each of the ten ARRL divisions plus a general manager for Canada. These positions would be filled in an election to be held in April 1924, the ARRL’s tenth anniversary year.

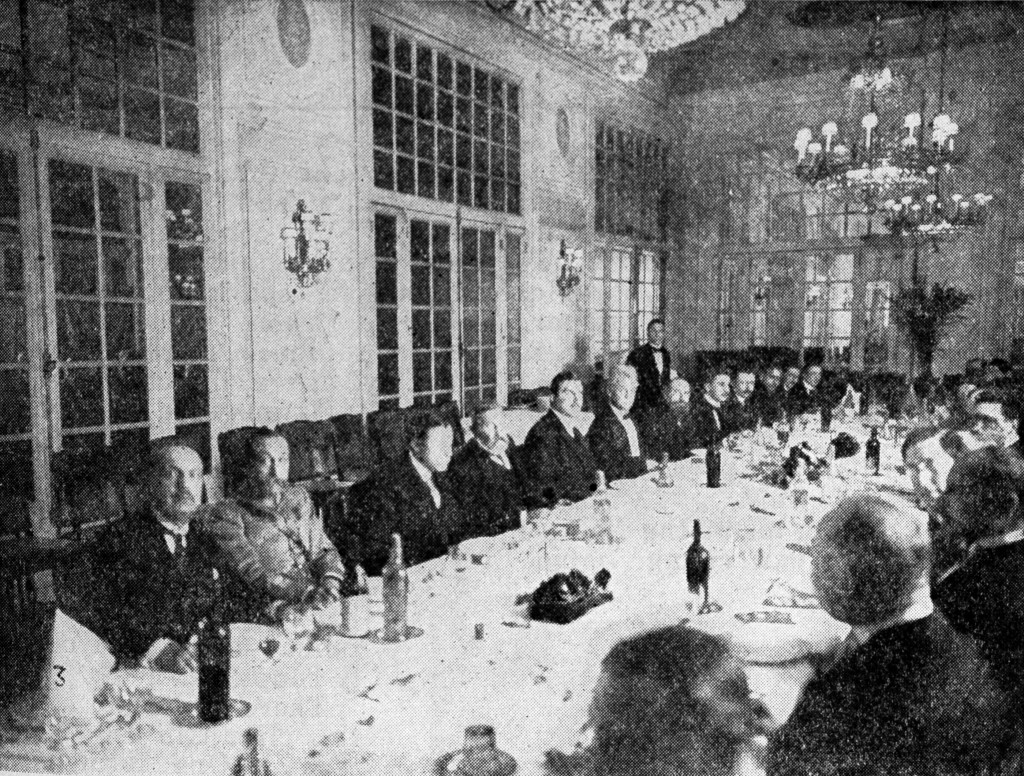

Paris Dinner Meeting, 12 March 1924. Maxim is seen at the table, sixth from left.

As international amateur radio communication took off, Maxim set sail for Europe to confer with his counterparts from other national amateur radio organizations.4 In Paris on 12 March 1924 the group held a dinner for him, organized and chaired by Pierre Corret, chairman of the Inter-Society Committee formed by the three French radio societies during the transatlantic tests. The dinner was also an international amateur radio meeting, the first of its kind, and included representatives from nine countries: Belgium, Canada, France, Britain, Italy, Luxembourg, Spain, Switzerland, and the United States. Denmark, unable to send a representative, sent a letter of support. After dinner, Corret called the meeting to order and spoke in high praise of the ARRL and its president, saying the rest of the world looked to the League for leadership in organizing international amateur radio. Maxim followed with a direct call for the establishment of an international amateur radio organization. Everyone in attendance naturally agreed—that was what they had assembled for—and Maxim was asked to organize a committee to begin the process. Two days later, the Temporary Committee of Organization, a group of representatives from each of the countries present at the dinner, met to work out preliminary details. They elected Maxim president and Corret secretary, and decided to name the new entity the International Amateur Radio Union. All other countries would be invited to participate in a formal congress, to be held in the spring of 1925, at which they would consider a constitution based, in part, on recommendations solicited from the ARRL. As planned, the new ARRL directors were all elected by their respective division members in April, and took office on 1 July 1924.5 Later that month the League’s board endorsed the creation of the IARU as it unanimously reelected Hiram Percy Maxim and Charles Stewart as president and vice president to take the ARRL into its second decade.6 The board also chose to highlight the progress of amateur radio over the previous ten years by recognizing the organization’s founder. With Stewart presiding, the first resolution of the new board was adopted, praising Maxim and recognizing his “devotion, sincerity and ability” as having been pivotal in the success of the League, and resolving to “tender to Mr. Maxim this unanimous expression of our confidence, love, esteem and appreciation.” ![]() The first and organizing Congress of the International Amateur Radio Union was set to run from 16 to 20 April 1925 in Paris.7 To deal with the language problem the body would adopt a “formal international diplomatic procedure” consisting of written monographs, which would be handled by subcommittees. They, in turn, would combine their results into a draft convention to be approved by the full congress. All amateurs were invited to participate in the IARU. However, since it would be a federation of national organizations, only formal representatives of those organizations would have voting privileges. The League itself would send two official delegates, and individual League divisions and other US organizations were also planning to send one of their members to the meeting to assist. The ARRL organized a traveling party so that the North American contingent could sail together from New York aboard the Mauritania on 1 April, arriving at Cherbourg six days later. They planned to return via England on the Berengaria from Southampton, arriving back in New York on 1 May. A travel agent handled everyone’s arrangements. The estimated cost per traveler would be $600 (equivalent to about $8,000 in 2014) including meals, hotels and other expenses, and with four hams to a cabin for inside staterooms, second class. One could also fly from Paris to London as part of the return trip for an extra charge of $14.

The first and organizing Congress of the International Amateur Radio Union was set to run from 16 to 20 April 1925 in Paris.7 To deal with the language problem the body would adopt a “formal international diplomatic procedure” consisting of written monographs, which would be handled by subcommittees. They, in turn, would combine their results into a draft convention to be approved by the full congress. All amateurs were invited to participate in the IARU. However, since it would be a federation of national organizations, only formal representatives of those organizations would have voting privileges. The League itself would send two official delegates, and individual League divisions and other US organizations were also planning to send one of their members to the meeting to assist. The ARRL organized a traveling party so that the North American contingent could sail together from New York aboard the Mauritania on 1 April, arriving at Cherbourg six days later. They planned to return via England on the Berengaria from Southampton, arriving back in New York on 1 May. A travel agent handled everyone’s arrangements. The estimated cost per traveler would be $600 (equivalent to about $8,000 in 2014) including meals, hotels and other expenses, and with four hams to a cabin for inside staterooms, second class. One could also fly from Paris to London as part of the return trip for an extra charge of $14.

![]()

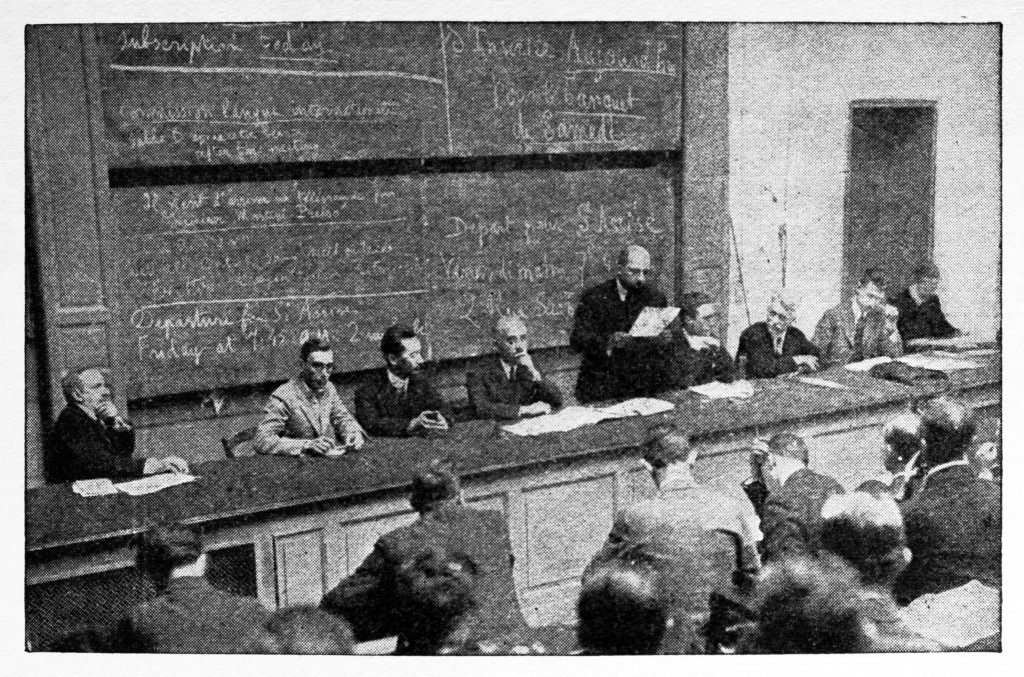

Thirteen months after Maxim proposed the idea of an international amateur radio society, the first International Amateur Congress was called to order in Paris at the Faculté des Sciences on 14 April 1925, coincident with the International Radio Legal Committee.8 The two organizations held a joint opening session in the morning, then went their separate ways that afternoon.

First IARU Congress, Paris, 1925.

Amateurs from twenty-three nations attended: Argentina, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, France, Finland, Germany, Great Britain, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Luxemburg, Netherlands, Newfoundland, Poland, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Uruguay, and the United States. Some French attendees had expected the IARU to include broadcast listeners and engineers, and were disappointed when they learned it was to be all about transmitting amateurs, a term increasingly used to distinguish amateurs from other kinds of radio hobbyists. The Americans were expecting the European amateurs to be mostly older and interested more in experimenting than operating. “This was all wrong; the French amateur when we really found him, and all the rest of them, are just like ourselves, a noisy, happy bunch of keypushers of our own age, tooting whistles and discussing circuits, and talking ‘QST English,’ bless ‘em!”, wrote Warner. “And so we are happy to record that we found the hams from all around the world all alike in complete agreement as to what they wanted, and looking to Mr. Maxim to lead the way.” In addition to Maxim and Warner, the North American delegation included Mrs. Maxim as interpreter, Jimmie Morris, 4IO and Gordon Hight, 4BQ (Southeastern Division), Lloyd Jaquet of New York City, editor of Amateur Radio magazine, Major Bill Borrett, c1DD, of Halifax, and L. Reid, 8AR, representing Newfoundland. After the opening joint session, subcommittees were formed to take on various organizational tasks. Each would operate democratically with one vote for each represented country. Subcommittee-1 dealt with the formation of the IARU itself. Its fifty members decided that headquarters would, at least temporarily, be located in the US, presumably since the ARRL was being used as an organizational model and would be providing its initial operational capability. QST was named the official organ of the IARU and it would debut an IARU News column in its July issue. The basic outline of a constitution was handed to the subcommittee members on 16 April. Maxim, Metzger, and Warner worked on a draft late into the evening at the Hôtel du Louvre. A large group of hams then “commandeered a flock of typewriters” and stayed up all night working to produce enough copies of the constitution in English and French for distribution to all the delegates the following morning.9 Warner skipped three meals in the process. The nineteen country delegates on the subcommittee reviewed and approved the draft, and later the full congress did the same. The following day the first IARU officers were elected by the delegates, “in a strictly ham meeting reeking with international good fellowship,” wrote Warner.

As first IARU member, Maxim hands his dues to Warner. Corret and Marcuse look on.

Although individuals could be members of IARU at the beginning,10 each country where there were more than twenty-five members would have its own section and president. The Board of Directors would consist of these presidents and an elected Executive Committee, very similar to the League’s board. Maxim was elected International President, Gerald Marcuse, g2NM, International Vice President. Jean Mezger, f8GO and Frank D. Bell, z4AA of New Zealand were appointed as Councillors at Large, and Warner was named International Secretary-Treasurer. Together, these officials made up the Executive Committee—all prominent amateurs active on the air in advancing the boundaries of international communication. Most notable was the election in absentia of Bell as a Councillor, by virtue of his well-known on-air achievements and organizational involvement at home. Once the voting was over, Warner “opened the roll for membership”—and Maxim became the first of 112 paying members. Other subcommittees dealt with on-air tests, international wavelength coordination, international language, call signs and intermediates. Some committees comprised of non-amateurs had their reports adopted but were “not binding upon the Union.” The Executive Committee would study them later.

Warner and friends with ham sandwich

On 18 April both congresses met and ratified all actions—and late arrivals from Russia and Indochina brought the number of participating countries to twenty-five. Amid enthusiastic applause, a bowl of flowers provided by Dr. Mertz of Switzerland was presented to Maxim, “in the name of the transmitting amateurs of the world.” The flowers were then distributed so that everyone could wear one in his lapel at the closing banquet. Knowing that Warner had skipped meals during the marathon constitution-writing session, the amateurs of Belgium and France presented him with a three-foot-long, ten-pound ham sandwich. Warner wrote that “the next night another little international ‘congress’ took it to a little sidewalk restaurant across from the hotel and there it was dispatched muy pronto, washed down with good beer, which didn’t happen to be against the law there!” Before leaving Paris the Americans toured some local stations, including FL at the Eiffel Tower. They then stopped over in London for five days and attended a dinner hosted by the RSGB. There they met Captain Rex Durrant of GHH1, often heard on the air from Mosul, Mesopotamia. Durrant was with the Royal Air Force and had tried to fly in for the Paris congress. But he was forced to land fourteen times en route due to bad weather, and only managed to make it to Marseilles by the final day. So he decided to continue on to England directly.

Post-IARU congress gathering at the home of Gerald Marcuse, g2NM, IARU VP.

Seated, L-R: Mrs Maxim, Jean Metzger f8GO, IARU Councillor at Large, HPM, Marcuse, Warner, and Mrs Marcuse.

Standing, L-R: Gordon Hight, 4BQ of Rome, GA, Major William Borrett, c1DD, of Halifax, NS, L. Reid, 8AR, of St. Johns, Nfld. James Morris, 4IO, of Atlanta, GA, Mr. Nicholls, g2CC [Photo courtesy of Connecticut State Library, Maxim Collection]

![]()

By the fall of 1925, the total IARU membership stood at only 698, with 264 from the US, “disappointingly small,” judged Warner.11 The original concept of a federation of national societies had morphed into an international organization of individual members, largely because some countries did not yet have an amateur radio organization. Most were now unhappy with this arrangement and expected it to change when more membership groups formed autonomous national societies 12. The next spring, the IARU announced a “New International Brass Pounder’s Club” – the WAC Club – Worked All Continents – “composed of brass pounding ether burners” who have worked at least one station in all six continents: Australia, Africa, Asia, Europe, North and South America.13 To be admitted, amateurs must send in QSL cards as proof, which would then “be returned together with the Official WAC certificate endorsed by the Grand High Wacker himself,” declared its secretary, presumably the current holder of that title. The organizational rearrangement took about a year, and in December 1926 the IARU announced the first steps in transforming itself into a federation. Each section larger than the twenty-five-member minimum would now collect and retain its own dues for use by its section members.14 Smaller ones could continue to pay dues to the international headquarters in Hartford. Meanwhile, more country societies adopted a variation on the ARRL diamond as their own logo.15

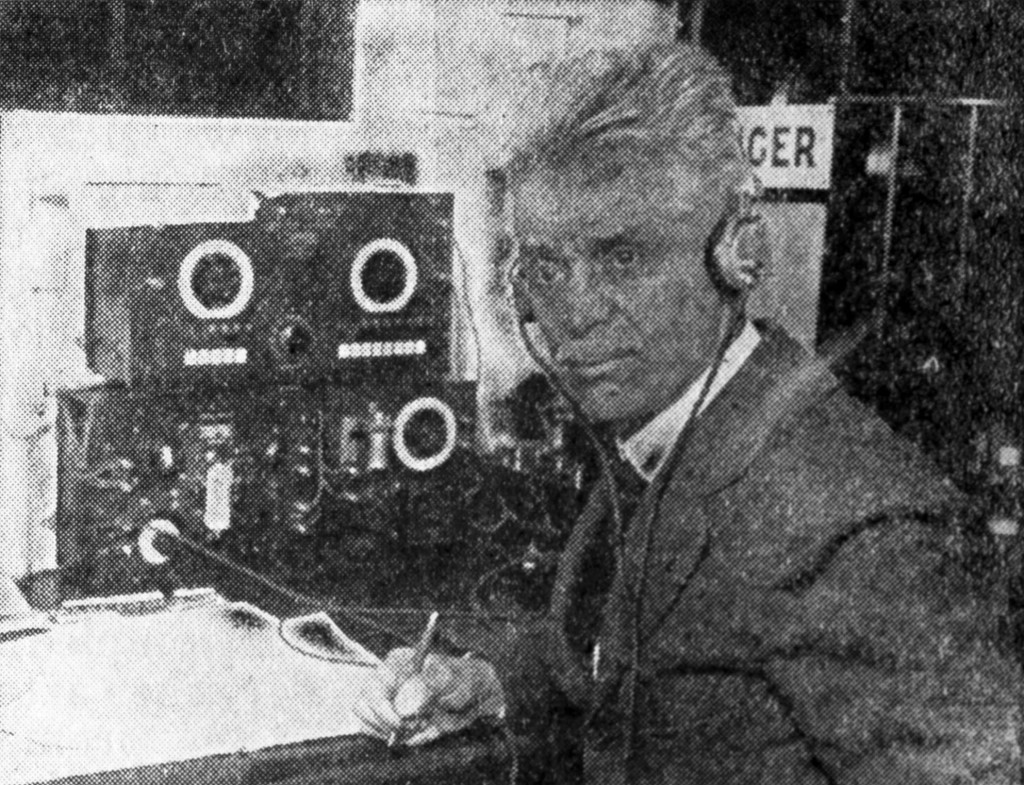

Maxim in the radio room aboard ship during his return voyage

RSGB officially became the British Section of IARU, and coincidentally the union announced that the British R system of audibility would be officially endorsed, and that GMT was to be used for all correspondence instead of local time. One ARRL director raised an issue with the use of GMT, which means Greenwich Mean Time, distinguishing it from GCT or Greenwich Civil Time. He pointed out that amateurs were actually using GCT which starts at midnight, whereas GMT begins at noon.16 It seemed a bit late to make an issue of this since the League and the IARU had both endorsed the use of GMT, and the use of the term seemed to be nearly universal, not just in amateur circles. Yet, Warner thought it necessary to advocate switching to GCT. The term would continue to be used in QST for a while until common convention prevailed. As amateur radio expanded worldwide, individual IARU membership became increasingly burdensome to maintain. In the summer of 1928 a new constitution was proposed to reorganize it into a union of country organizations, each of which would maintain its own membership.17 The remainder of the document was unchanged except to make its language conform to the new organizational model. By a vote of section presidents it was easily adopted on 30 October 1928, more than three years after the organization’s founding. In 2014, the IARU has grown to 162 member societies around the world. Still headquartered at ARRL in Newington, Connecticut, it is licensed to operate under its own call sign, NU1AW, from the Maxim memorial station, W1AW.

![]() de W2PA

de W2PA

- J. K. Bolles, “The Ham Lets Loose Both Barrels,” QST, November 1923, 12. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “International Amateur Radio,” Editorial, QST, February 1924, 7. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “Our New Constitution,” Editorials, QST, February 1924, 7. ↩

- H. P. Maxim, “The International Amateur Radio Union,” QST, May 1924, 16. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “Election Results,” QST, June 1924, 19. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “The Annual Board Meeting,” QST, September 1924, 22. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “All Aboard For Paris,” QST, March 1925, 26. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “International Amateur Radio Union Formed!,” QST, June 1925, 9. ↩

- The full IARU constitution is printed in June 1925 QST, page 14. ↩

- Membership was $1 US per year, separate from ARRL or QST. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “IARU Growth,” IARU News, QST, November 1925, 49. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “The I.A.R.U.,” Editorial, QST, September 1926, 7. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “A New International Brass Pounders Club,” IARU News, QST, April 1926, 54. ↩

- K. B. Warner, IARU News, QST, December 1926, 57. ↩

- K. B. Warner, IARU News, QST, May 1927, 61. ↩

- K. B. Warner, Editorial, QST, March 1927, 8. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “New Constitution Proposed,” IARU News, QST, August 1928, 60. ↩