Paul Godley slept well during his six-day Atlantic voyage, catching up on the sleep he lost during the intense organizing activities in the run-up to the transatlantics project. Arriving in England on 21 November 1921, he was unexpectedly met by H. J. Tattersall, Superintendant of the Marconi Company in Southampton, who helped him deal with various customs problems.1 A recently imposed import duty would have caused his equipment to be held up for weeks. Instead, they negotiated for Godley to leave a $100 deposit to be returned when the equipment again exited the country.

Moving on to London, he attended meetings of the Wireless Society and the Royal Society of Arts. There, he heard a lecture by Fleming, and met other people prominent in radio including Marconi, who expressed confidence in his ultimate success and asked Godley to pass on his regards to the American amateurs, telling him, “I, too, am but an amateur!”

A group of local hams arranged a dinner in Godley’s honor, where he was surprised to meet two “O.W.’s” among the attendees. Despite the group’s hospitality, he still detected in their demeanor that the British hams were “unable to decide whether I was just a ‘nut’ or whether I was really confident of our ability to put the thing over.”

An article appeared in the London Star on 30 November describing the events leading up to the test. Its author asserted that Americans blamed the failure of the February tests on incompetence of the British hams (as well as QRM from oscillating regenerative receivers), and that was why they had sent over “one of their hardest of ‘hard-boiled hams’ with a brand-new bag o’tricks and their good wishes. He will show us how it should be done,” they wrote. Godley later remarked dryly, “And now you know why I went to Scotland!!”

Godley had the opportunity to have a broad discussion of amateur radio with E. H. Shaughnessy, chief engineer for the wireless section of the General Post Office (GPO)—the main radio authority in Britain and the body responsible for the severe operating restrictions in effect at the time. The official believed that wireless operation such as existed in the US could not work in Britain because of the island’s comparatively small size and its proximity to foreign countries—they would have to consider effects on international communications. He was also amazed at the rapid development of radiotelephone broadcasts in the US and dubious of such a possibility in Britain.

Despite Shaughnessy’s skepticism, Godley was confident that eventually the restrictions there would be lifted once the British public began to understand the possibilities of radio in public hands. It was something he was certain had not yet been fully grasped in the US, either, even by amateurs, writing,

I wonder if even here in America we amateurs realize that today the state of the art makes it possible for the President of these United States to speak directly to every citizen in the land? One’s imagination cannot help but see the immense value of such an arrangement during times of national peril.

He fully appreciated the impact a successful transatlantic crossing could have.

At the Wembley Park home station of Commander Frank Phillips, one of his English hosts and designer of the grand prize Burndept III receiver, Godley set up some of his equipment to have a listen to the local radio environment. He did not like what he heard. Below about 275 meters, harmonics from high power commercial stations filled the London air waves. On one GPO station in particular he was amazingly able (and “highly amused”) to count thirty-nine harmonics. He was also surprised and dismayed to hear the high level of QRN, which was mostly nonexistent during winter in the States.

The harmonic QRM, the intense QRN and five days of foul weather in London all convinced him to move to Ardrossan, a small fishing village twenty miles west of Glasgow in Scotland, a site he had already chosen as an alternate. The Londoners warned him just how miserable Scotland would be at this time of year, including the “ill effects of the Scotch whisky which one would most certainly be unable to dodge.” But his mind was made up.

He now needed a permit extension to be able to operate a receiver in Scotland. After failed attempts by British test organizer Phillip Coursey and others to get one, Godley decided to go to the GPO himself and managed to see an assistant secretary named J. W. Wissenden who, after intently listening to his story, was able to get the permit issued2 and arranged for it to reach Glasgow in time for the planned start of operations.

On his way north, Godley took a side trip to Aberdeen at the request of the R.C.A. committee investigating the 2QR reception report. His visit partly contributed to their eventual findings. There he met the Miller brothers at their electrical shop, then drove into the countryside to meet Benzie at his station. Impressed with Benzie’s antennas and enthusiasm, in spite of being handicapped by a lack of sophisticated equipment, Godley later wrote, “He had the bug badly, and would come nearer to feeling at home were he to be suddenly dropped into the thick of amateur activities on this side than any other whom I met.” He complemented Miller and Benzie for their “sportsmanlike spirit,” as well as that of the Robinsons in the US. The British amateurs’ consensus view seemed to be that the two had very likely only heard a British amateur station.

Arriving in Glasgow on Saturday evening, 3 December 1921, Godley slept late into Sunday morning in an attempt to shake off an oncoming head cold. The temperature was near freezing there and his hotel room at the Central Station Hotel was unheated. Sick, tired, and cold, he now had three days to get ready.

The next morning he met his local contacts, picked up new supplies including a tent, and boarded a train for Ardrossan in late afternoon. Arriving, he checked into the Eglinton Arms Hotel. The awful weather, which had been a constant, cold rain, eased somewhat toward evening. With only thirty hours to go until the tests were to begin, Godley went out that night to scout beach locations that looked promising on the map as ideal ones for putting up his Beverage receiving antenna. To his dismay, he discovered both local beaches were at high tide and flooded. Using them would be impossible.

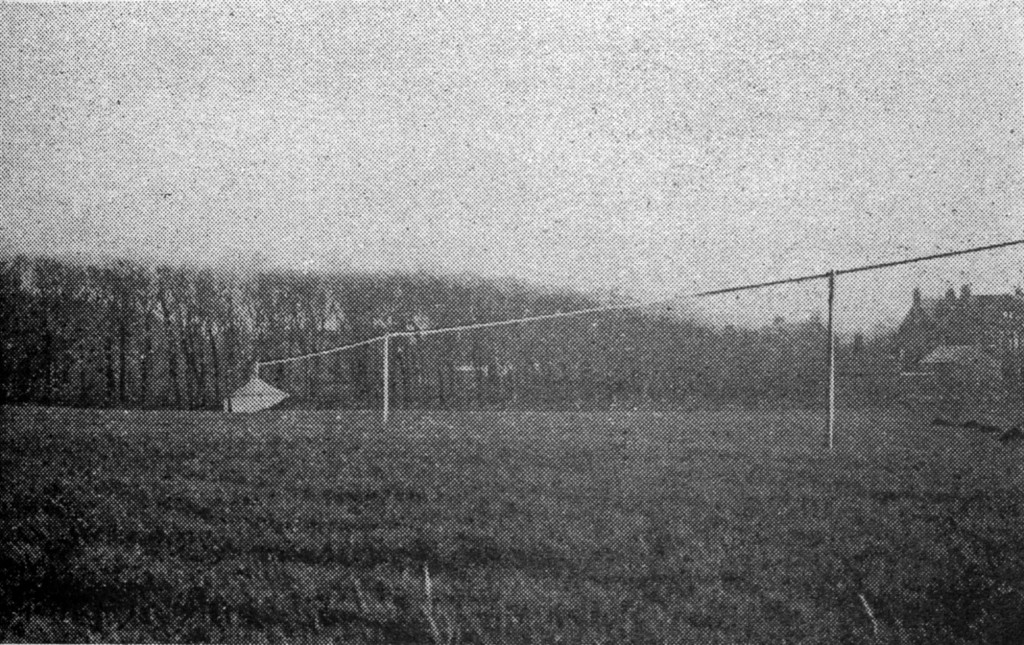

Operating tent and Beverage wire feed point

In a driving downpour the following day, and with the help of some local officials, he at last found an empty field that looked usable. After a brief respite at the hotel to warm up, they set off again to talk with the land owner. “I had been congratulating myself all along on the good fortune of having two interpreters with me,” he wrote, “because I must admit I found considerable difficulty in understanding English as spoken in Scotland.” The land owner, Mr. Hugh Hunter, was excited by the project and eagerly allowed them the use of his field.

The Marconi Company’s Inspector D. E. Pearson, who would act as “checking operator” with Godley during the operation, joined him in Ardrossan to help get set up for the test.

Hunter’s field was slippery with seaweed used for fertilizer and walking was difficult as they began assembling the receiving station. A horse-drawn wagon carrying the supplies had trouble reaching the set-up location and had to be partly unloaded some distance away. They put down floor boards over the mud and raised the tent which promptly blew down. Pre-built two-by-four beverage poles they had bought in Glasgow were spread out into the field. They had prepared enough poles and wire for a 1300-foot Beverage wire, 12 feet up, along a line oriented 26 degrees north of west—“directly towards 9ZN.”

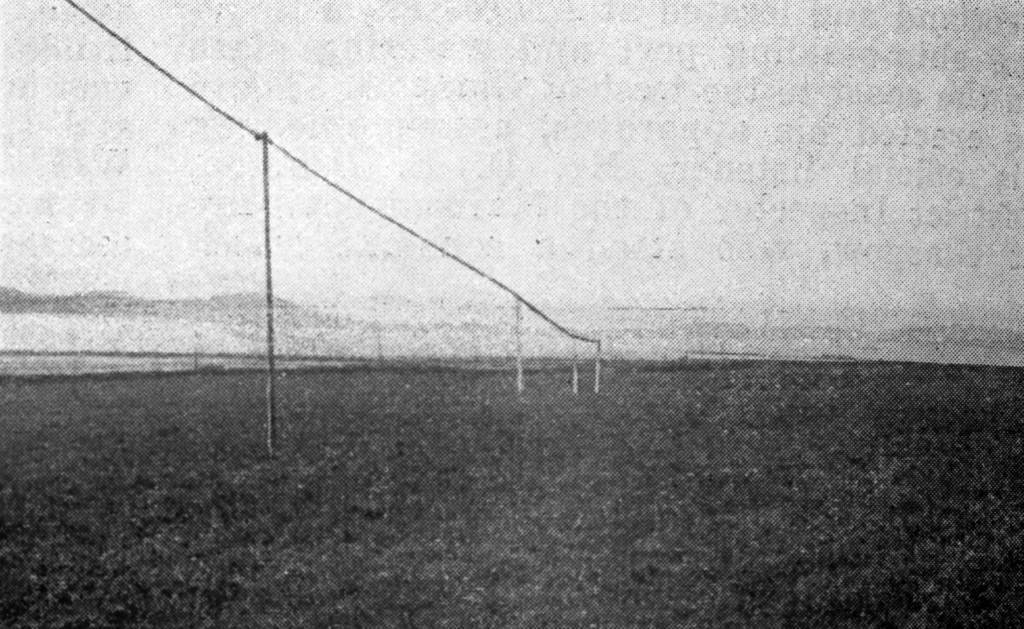

Beverage wire antenna pointing toward the North Atlantic

By 4:00 p.m. it was dark and still raining but they continued to work until 6:30. Later that evening, back at the hotel, Godley connected a receiver to a 60-foot antenna wire and heard many 600-meter stations and far less noise than in London. Exhausted and disappointed at not getting operational as originally planned, he retired for the night, at least reassured that the improved on-air conditions had justified his move.

They were back out at dawn on 7 December, and with additional local help worked all day setting up the receiving station. By nightfall at 4:00 all the poles were up and the Beverage wire had been strung. They continued to bury ground plates and connected a variable, non-inductive resistor to complete the antenna. After a quick dinner at the hotel, they returned to hook up the receiving equipment. Everything was working so far, and just before midnight they were receiving signals from European stations including FL in Paris, POZ in Nauen, Germany and many more on 600 meters.

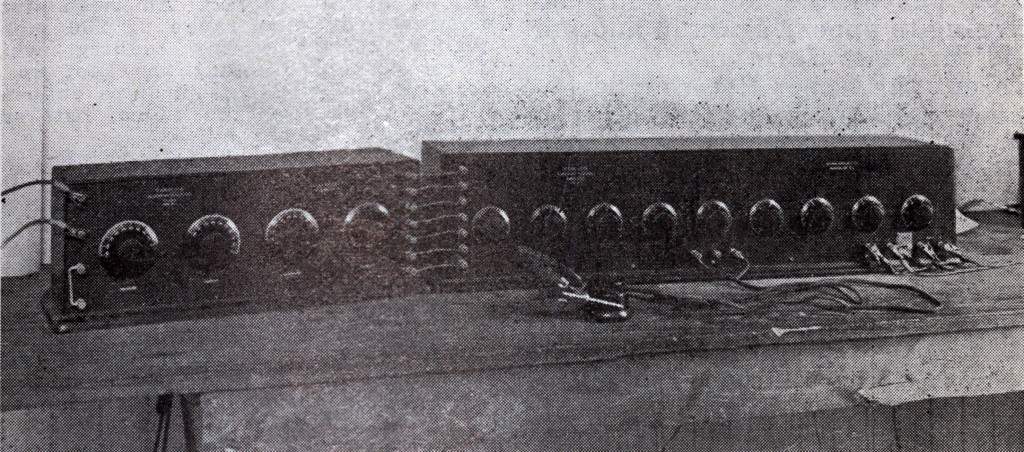

The receiving equipment included a Paragon regenerative receiver with a DA-2 detector-amplifier and a 10-tube superheterodyne receiver with external beat oscillator for CW. A 60-foot wire was put up in a tree and the incoming 600-meter signals were used to tune it up for maximum sensitivity on shortwaves. Around 1:00 a.m. they began listening on the Beverage, hearing a few commercial harmonics as expected, but far fewer than in London. The Paragon connected to the Beverage mirrored the unplanned handshake between the two inventors aboard the Aquitania.

Godley’s superheterodyne receiver

Only a half hour into listening they already began to hear signals unmistakably coming from the US, possibly identifying 1AEP and definitely 1AAW on 270 meters. The signals were fluctuating between too weak to read and booming in loudly, but Godley and Pearson were elated, having achieved their primary goal on the very first night! They took a break around 2:30 to inspect the antenna and repair a wire break and a downed pole caused by the high winds. Hearing no further signals from the US and rising QRN, they quit, tired but happy, at 6:00 a.m. after 21 hours of continuous work in the cold wind and rain.

Although the weather finally cleared the following evening, 8 December, they heard no amateur signals at all. Some 600-meter signals were noticeably weaker than on the previous night indicating that conditions were probably worse overall. CW reception was particularly hindered by harmonics of high power stations, especially the one at Clifden in Ireland.

As the clear weather chilled further, Godley’s head cold worsened. “Pearson being a Scotchman seems to be immune,” he wrote, “and no doubt would suggest that I don’t drink enough of Scotland’s Honeydew.” They closed down at 6:00 a.m. after a futile night of noise-filled listening.

The rain returned on 9 December, and after listening for free-for-all spark signals, they switched to CW and immediately heard 1BCG very steadily around 12:50 a.m. on 230 to 235 meters plowing right through the QRM from Clifden. His signals improved even more after adjusting the Beverage. “He is calling ‘PF test’ and signing. Sweetest song I have ever heard,” wrote Godley excitedly in his log, “He fades out for 30 seconds every 3 or 4 minutes but always comes back strong and steady.”

Godley had chosen the Beverage antenna after hearing the high QRN in London, and abandoned plans to also erect a vertical. They tuned the Beverage by running back and forth from the operating tent to the far end where the variable resistor was located. He later speculated that, since on the ninth they had optimized it on the signal from 1BCG and then left it there, this was the only wavelength for which it was ever properly adjusted.

They shut down at 6:00 a.m. after hearing no other stations, but started up again briefly just to copy MUU. Upon hearing it sending “Godley’s message,” he was struck by the reality that they were indeed making history. Suddenly feeling held back, he wrote, “I would give a year of my life for a 1-KW tube transmitter … aerial .. license… To be forced to listen to a Yankee ham and only listen is a hard blow.”

The New York Times reported the news on 10 December without detail, saying that “between 15,000 and 20,000 amateur radio stations in the United States are taking part.”3

Godley wired Coursey with the report of hearing 1BCG. Greatly impressed by the quality of its signal, he and Pearson speculated about what equipment that station could possibly be using, with Pearson unable to believe it was less than 1 kW. The signals had been so “unusually steady” (in frequency) that he was able to take advantage of resonance in the headphones to boost its readability—not knowing that was exactly what its designers had hoped for. So good was the signal that Godley was able to detect an operator change, presumably by changes in fist, the particular style with which each operator sends Morse code.

He decided to wire Armstrong directly to suggest he try sending a message the following night. But Godley’s message was mishandled and came through as “send MGES.” So the following night with signals coming in very well, instead of sending actual messages 1BCG comically kept sending “MGES” over and over all night long through fading and static (and reflected in Godley’s running log annotated with time stamps).

They heard and identified several other stations on both CW and spark that night, including many who were calling other stations. 9ZG was recognized by fist though he was not heard to sign his call. After a productive night of listening and logging, they closed down at 6:50 a.m. to copy MUU.

Godley cabled 1BCG with a copy of his note to Coursey. He imagined the gang there rejoicing at their success as he and Pearson marveled at the performance of 1BCG, the highlight of the test and steadily the strongest, most constantly copyable signal.

Many other stations were heard that night but not identified, sometimes simply because they failed to sign their calls while making local contacts, a practice Godley made a point of condemning. Between 4:30 and 6:00 a.m. there were sometimes so many stations coming through at Ardrossan that the QRM made copying difficult. It reminded him of familiar conditions around New York, but with much weaker signals.

The next night, Monday, 12 December, they again heard lots of weak stations and identified many from the first and second district, on spark, CW or ICW.4 Everything faded out completely by around 4:00 a.m. On Tuesday, Signals had been coming through in London as well, and Coursey radioed ARRL headquarters with, “Many your stations heard by British amateurs. Details later.”

Godley and Pearson, having been awake for 24 hours, overslept and did not begin operating until 1:30 a.m. that night. Although the weather was clear, on-air conditions were poor and they heard no identifiable signals from the US.

On 13 December into the fourteenth, they slept late again. According to a letter from Coursey, US stations had been heard in London in the early morning on modest equipment, but mostly hearing QRM from harmonics and commercial stations.

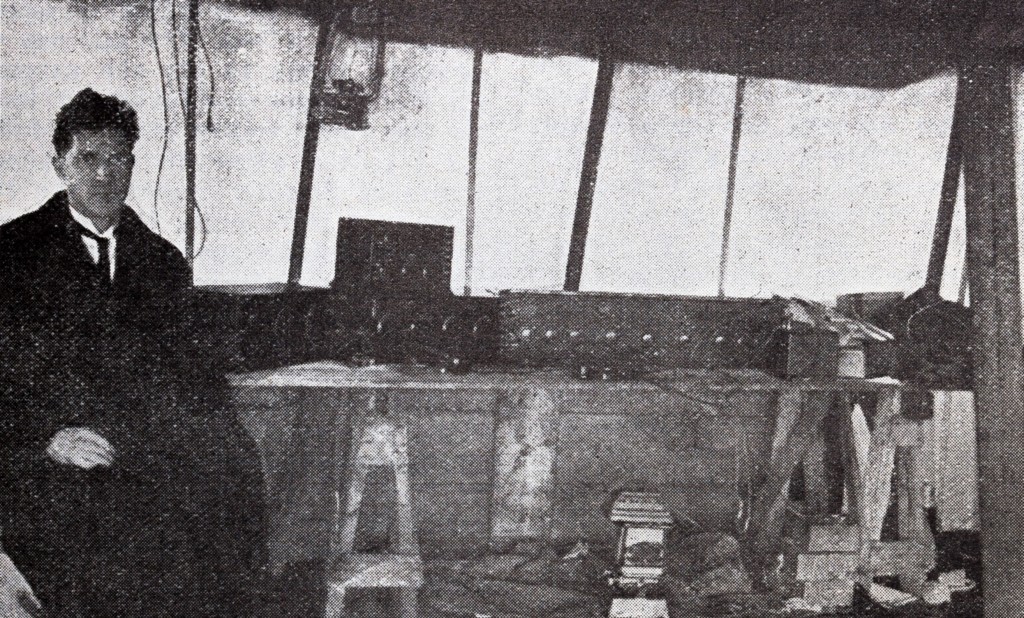

It was overcast, and still quite cold and windy. The oil heater was not working well so they moved it under the operating table. They then arranged the equipment to permit them to crouch down near the heater with their heads just above the table, so that “the greatest possible portion of our bodies was exposed to what little heat was radiated by the stove.” At one point, they both fell asleep against the desk. As they slept, the stove began to smoke. Godley awoke suddenly, startling Pearson who gave him a strange look. Some of the papers along with the underside of the table had turned black, and so had the portion of Godley’s face that had lain across a crack in the table. After another disappointing night of hearing no signals, they quit at 3:10 a.m. “very tired and sleepy… both greatly in need of rest.”

D. E. Pearson, in the operating tent at Ardrossan

At times they were so tired it was difficult to go outside to check the antenna. The static, the harmonic QRM, the cold and wet were hard to endure. Godley was also battling a worsening head cold that taxed his energy. Fearing pneumonia, he considered quitting but was inspired to continue by Pearson’s operating ability and enthusiasm. And, of course, the signals coming through kept them both excited and interested.

Wednesday, 14 December into Thursday, the weather was finally beginning to warm just a bit. But light static, commercial stations and harmonics were all that they heard, with very few signals of any kind coming through. They quit early again at 4:30 a.m.

The following day they were “up all day getting photos of set-up; also had several visitors,” one of whom voiced incredulous disbelief upon being told where the various signals were coming in from—“I know a bit o’American swank when I see it,” he said. With much worse static that night they shut down at 4:40 on Friday morning after another session without hearing any US signals at all.

Godley originally intended to return home by Christmas to spend it with his family. But once he decided to operate from Scotland he realized that it would not be possible. He could not get back to Southampton in time to catch the Aquitania on 17 December due to the schedule they had set up and the extra travel involved. So, before going north he had booked himself on the Olympic, scheduled to sail on the twenty-first. Now he could use the extra time to “pay proper respects to various men who had been of great assistance,” get his equipment through customs, and retrieve his deposit.

He’d have to make it to London by Monday the ninteenth in order for this new schedule to work out. So, on Friday afternoon he and Pearson decided to forego another night of listening in favor of dismantling the station. That way Godley could return the equipment he had borrowed in Glasgow before everything closed down there, as it normally did at noon on Saturdays. By early Friday evening everything had been packed up and later that night they were back in Ardrossan, ready to board the train to Glasgow in the morning.

Besides the schedule advantages, they later were glad they had quit when they did because the tail end of a cyclone hit Scotland that night bringing higher winds than at any time during the operation. The same storm had flooded London and battered the Olympic on her way in, causing two deaths aboard and damaging equipment. Godley speculated that the storm might have actually played a part in the success of the tests. It had originated in the Gulf of Mexico, proceeded up the east coast of North America, crossed the Atlantic and brushed by the British Isles before going on to Norway. That meant the storm had been located between their receiving station and the US East Coast during the time when they had heard the largest number of signals.

The editor of the popular British science magazine “Conquest” sent Paul Godley a poem during the test that neatly summarized his various trials:

If our climate is un-Godley,

If the weather seem to Paul,

If our static strikes you oddly,

If you hear no sigs at all,

If you get harmonics down the scale,

As far as tuners go,

If the dialect in Scotland,

Doesn’t sound like Ohio,

If twenty thousand hard boiled hams

Are waiting on your word,

If but the thought of hearing them

Seems very near absurd,

If, – in the chilly morning hours, –

The faintest sigs come thru,

We’d like to hear about it,

If it’s all the same to you!!

de W2PA

- Paul F. Godley, Official Report on the Second Transatlantic Tests,” QST, February 1922, 14. ↩

- The permit was reprinted as part of Godley’s article in February 1922 QST. ↩

- “Amateurs Send Radio Far,” The New York Times, December 20, 1921. ↩

- Interrupted CW, a way of modulating or pulsing a straight or undamped CW signal to make it audible in a receiver having no beat oscillator. ↩