After the initial thrill of being the first to hear transatlantic signals, Paul Godley’s next thought was of making contact, and a helpless frustration at not having equipment to transmit a reply. And now, emboldened by the successful second set of transatlantic tests in December 1922, many amateurs were talking about the possibility of a first two-way contact across the ocean.

In fact, in early 1923 US hams were already informally running two-way tests with Leon Deloy, French 8AB (one of the European stations most widely copied in North America last time), without success, but with both sides hearing each other at different times.1 Deloy had also started a series of his own tests every Sunday, Tuesday and Thursday, transmitting between 0500 and 0530 GMT, then listening for thirty minutes.

Later in the year he reported experimenting all the way down at 45 meters.2 Deloy was hearing signals in Nice sent by an experimental station in Paris 435 miles away, in broad daylight with signals readable 16 feet from the phones, no QSS, and very little QRN. He believed that signals of equal power at 200 meters or higher would not have been readable at all. It was a just hint of things to come.

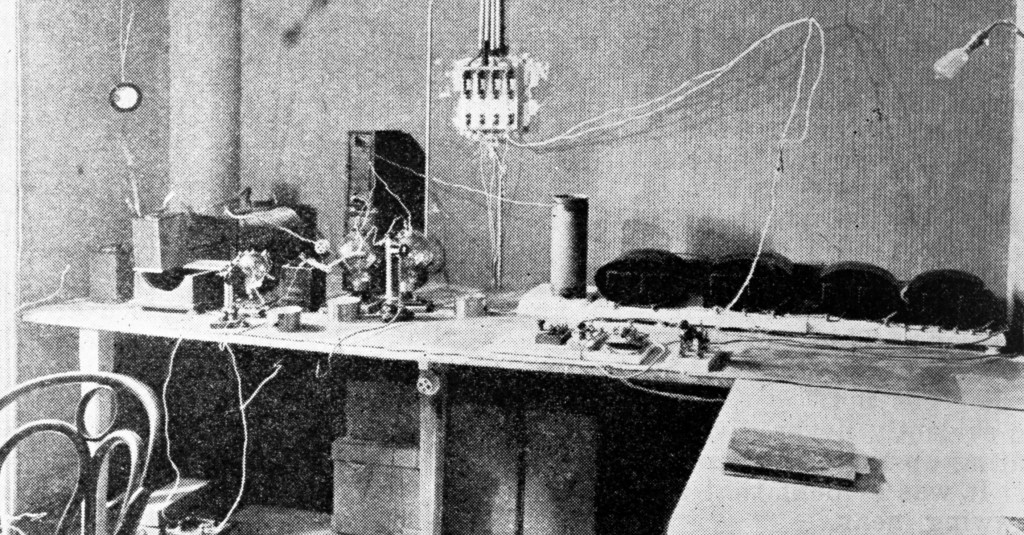

Deloy’s nice Nice experimental shortwave station 8AB

In the US several individual amateurs had been testing as well, exploring shorter wavelengths in a sort of inverted mountain climbing procedure. The explorers would first rendezvous at base camp at 200 meters and then tentatively descend lower in stages.3 Aside from the freedom from QRM—the short wavelengths were mostly empty except for commercial harmonics—they all found that the strongest signals came through below 170 meters.

To stimulate more such exploration, the ARRL Operating Department announced a 100 meter CQ party for the nights of 24 and 25 March 1923, from 10:30 p.m. to 12:10 a.m. Eastern Time, with ten minutes of transmitting time allotted to each US district plus Canada. Trying to encourage efficient operation, ARRL Traffic Manager Fred Schnell warned, “Don’t call CQ 185 times and sign once; no one is going to camp on your wave forever—keep signing at intervals. Everybody is invited to try both sending and listening and to send the logs to the QST Shop. They must be clean logs—not logs written on scrap paper or in the middle of a letter.”

Hams turned out enthusiastically. Logs arrived at headquarters from all districts except the seventh, as recorded in a special edition of the Calls Heard section of QST, in which the editor reported that “the gang is absolutely ‘nuts’ about short waves.”4 All of the calls reported were heard between 80 and 190 meters. Every effort was made to eliminate harmonics of signals at 200 meters or higher that could have been mistaken for short wave signals, presumably so that only those who were actually taking part in the test would be credited with being heard.

All of these experiences fed enthusiasm as hams prepared for the fourth transatlantic tests, which were to run from 21 December 1923 through 10 January 1924. As in the previous test, selected stations in Britain and France would be allocated specific times to transmit code words. But this test would also differ from its predecessors in one significant way: complete QSOs would be their ultimate goal. Even the name of the event changed. “The two-way transatlantic test would be open to everybody—a free-for-all,” announced ARRL Secretary Kenneth Warner, meaning that, in addition to the allocated stations, everyone else would get a chance to participate.

Several things were coming together to favor success this time:5 The government now mandated evening quiet hours, a regulation put in place just a few months earlier. Europe would again transmit and no North American stations were allocated transmit times until 11 January when the two-way attempts would start. Any North American station caught transmitting during the quiet periods would be disqualified from all awards. The only exception would be in case of emergency.

Each night, the test would be conducted between 0100 and 0600 GMT. During the first two hours, any amateur in Europe could transmit between 180 and 220 meters. Then, from 0300 to 0600 individual designated transmitters would send their assigned code words, with British and French amateurs transmitting on alternating nights. Finally, on 11 January, everyone was to attempt two-way contacts (QSOs).

QST offered a “genuine Brown Derby” to the first American to make contact. And a collection of prizes worth $3,6006 was donated by various companies to recognize “the best reception records.” A Grebe four-tube, 250-watt transmitter was the top prize and would be awarded to the amateur who reported the largest total station miles, meaning the sum of all the distances of all the stations logged, each one counting only once. In the case of code word stations, that bit of information must be correctly copied and reported as well. Winning the top prize excluded an entrant from winning any of the other prizes.

Next after the Grebe were five more award groups, designated A through E. Within each group the top five places carried awards of equipment ranging in value from $200 for first place down to $20 for fifth. The Group A award was for the greatest distance of any single reception, B and C were for the greatest station miles with France or Britain, respectively, on any given night, and D and E were for the greatest station miles with France or Britain over the duration of the tests.

Each amateur would be eligible to receive only one award. As Schnell put it, “It is to be understood that this is purely a sporting event and there is no excuse for anybody to be unreasonable and expect to grab everything in sight.” Logs should be complete and contain at least call sign, code word (if any), date, time, and wavelength for each reception, and each entrant should indicate in which group they were competing. The logs would be due at HQ no later than 25 January, a mere two weeks after the end of the tests.

With the exception of the equipment awards, the overall structure of the test was beginning to look a lot like today’s on-air contests.

As in previous years there would be a friendly bet. This time Schnell would wager on the outcome with UK equipment maker and radio amateur W. W. Burnham. Schnell suggested the stakes would be a pair of green suspenders, based on any challenge Burnham cared to name. They ended up betting “a nice clock” that at least twelve stations from Europe would be heard in North America.7

Recalling the QRM problems in the previous tests, Warner stressed the need for discipline during the upcoming round. He reminded everyone how embarrassing it had been when many stations, including some prominent ones, refused to stand by during the designated listening periods leading to a failure to copy more than just a few European signals “thru the merciless interference caused by the morons in our midst.”8 This year’s test would concentrate on receiving, before any two-way attempts. “These tests are an international sporting event,” repeated Warner, “and the whole world is invited to participate—but in listening, not in sending,” a tall order for hams eager to hit the key.

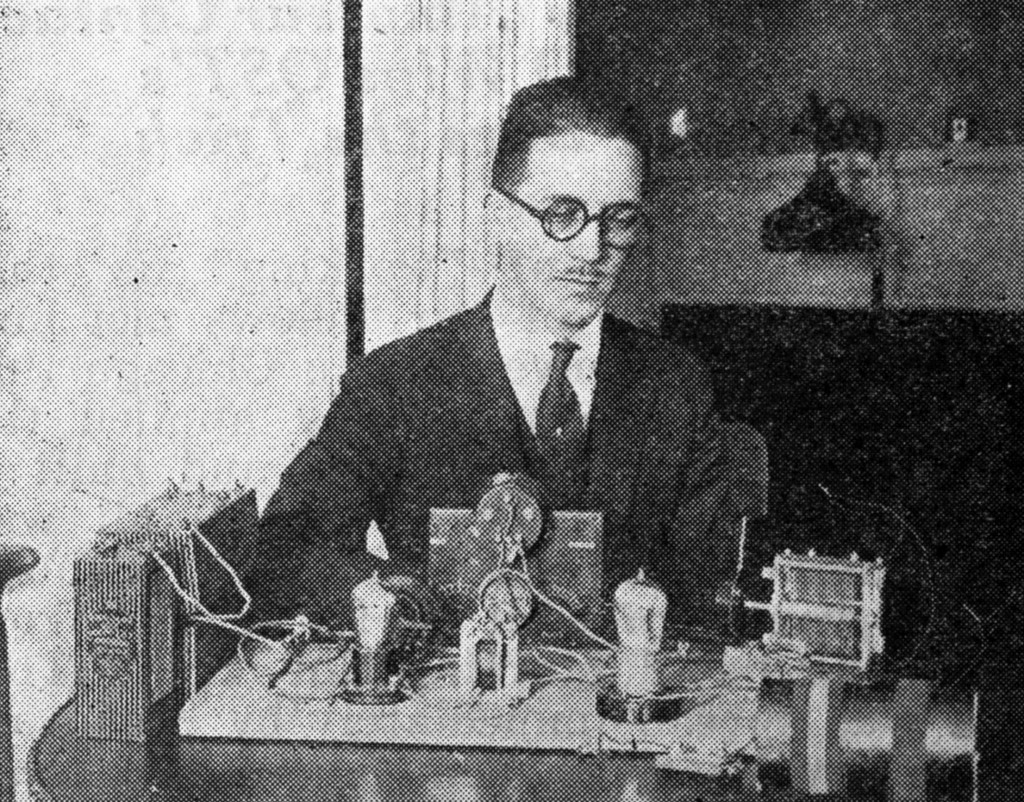

Leon Deloy, 8AB

One amateur taking the challenge particularly seriously was Leon Deloy, who spent a month traveling in the US attending the ARRL convention and visiting various American amateur radio stations in order to study them and prepare his own station, which he hoped would be one side of the first amateur two-way contact between Europe and North America.9 He knew of several other hams in France also building 1-kW stations specifically for the tests and wanted to get an edge over his competitors. “It will be more than a radio achievement; it will be one more tie of friendship between the two great nations which have been brought so close together by the late war,” he wrote.

Seeing the same level of enthusiasm in the US as in France, Deloy also took note of the differences in amateur operations in the two countries. For one thing, the average amateur was much younger in the US. For another, on-air operation was more “business-like” in that US amateurs concentrated on message handling (which was not even allowed in France), whereas the French amateurs emphasized experimenting. Transmitters in the US were often remotely controlled, but in France they were nearby where operators could get their hands on them—as an experimenter should. American amateurs optimized their receivers for ease of operation, useful in message handling, whereas in France they emphasized sensitivity and had receivers that were “most of the time spread all over the table,” wrote Deloy, which led to “difficulties in adjustment and lower reliability, but I think we very nearly get the maximum sensitivity possible out of our sets and most of us like far better to experiment with new hookups whenever we please than to sit night after night in front of the same nicely finished cabinet.”

He thought it quite a shame that spark was still allowed in the US—it had been banned in France.

The building, the traveling, the conversations, the research—a year or more of patient, painstaking preparation was all coming together in the fall of 1923. But the wait for the January transatlantic two-way tests proved to be too long for Monsieur Deloy.

Shortly after he returned from his trip to the US, he began preparing to try. Via telegram to Schnell he announced his intention to transmit on 100 meters from 9:00 to 10:00 p.m. Eastern US Time, beginning on 25 November. The word was then spread via broadcasts. Having just built a new tuner, Schnell was ready and listening on 100 meters the first night and copied 8AB immediately.

Commenting later on that scheduled reception10, Warner wrote that his tuner, “the most goshawfullooking haywire receiver you ever saw, had hurriedly been assembled … At the appointed hour there Deloy was, right from the first dot, readable all over the house. Wow, did this short-wave stuff work!”

Fred Schnell at 1MO

Deloy continued to call “ARRL” for an hour, as arranged, along with his cipher group “GSJTP.” He was notified (by other means) of the good copy and the next night he sent two messages that were copied by both Schnell at 1MO and John Reinarz at 1QP. The first message ever sent from France to North America via amateur radio read:

NICE FRANCE

A.R.R.L.WANT THIS FIRST TRANSATLANTIC MESSAGE TO CONVEY MOST HEARTY GREETINGS OF FRENCH TO AMERICAN AMATEURS.

LEON DELOY

The second message suggested a scheduled two-way contact. 1MO immediately asked for and received permission by the Supervisor of Radio to test on 100 meters—all was ready. The following night Deloy called again for one hour starting at 9:30 p.m. Eastern Time, sent two messages, and ended by asking for acknowledgement (QSL). Schnell then sent a long call on 110 meters and immediately heard Deloy replying.

Not quite ready to believe it, Schnell and Warner, who had joined him at his station, suspected it might just be a coincidental blind transmission, not a reply at all. “Will the fellow never end his call and say something!” wrote Warner, “Aha, he breaks! And then, my lads, came the first transocean R, R, R in all amateur history! Oh boy, oh boy, was that a thrill?”

The history-making first inter-continental amateur QSO was in the log! Deloy’s first in-QSO message to Schnell was:

R R QRK UR SIGS QSA VY ONE FOOT FROM PHONES ON GREBE FB OM HEARTY CONGRATULATIONS THIS IS FINE DAY MIM PSE QSL NR 1 2

This meant he had received Schnell’s transmission with signals that were readable and very strong, being heard one foot away from the headphones on his Grebe receiver. “MIM” is the alphabetic equivalent of the Morse code for a comma. Lastly, he asked for an acknowledgement of his messages numbered 1 and 2. At 1MO, 8AB was coming through equally well, copyable on Schnell’s loudspeaker from twenty-five feet away.

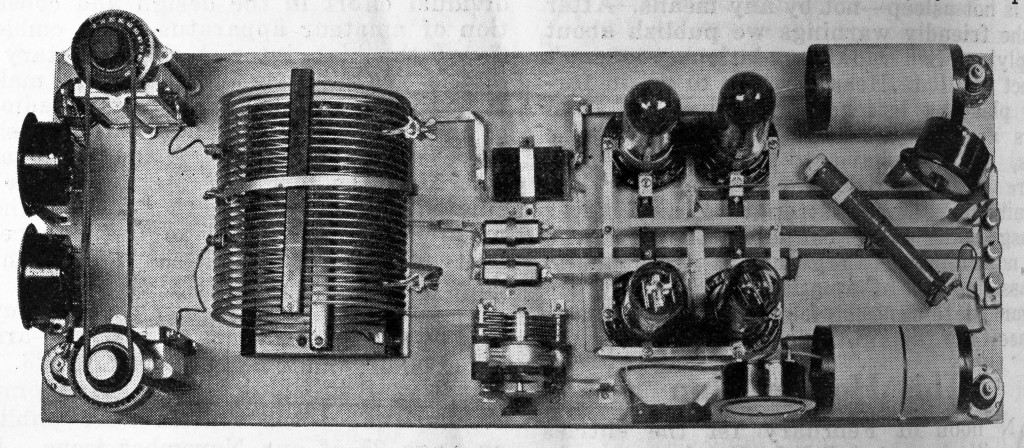

1MO transmitter used for first DX contact

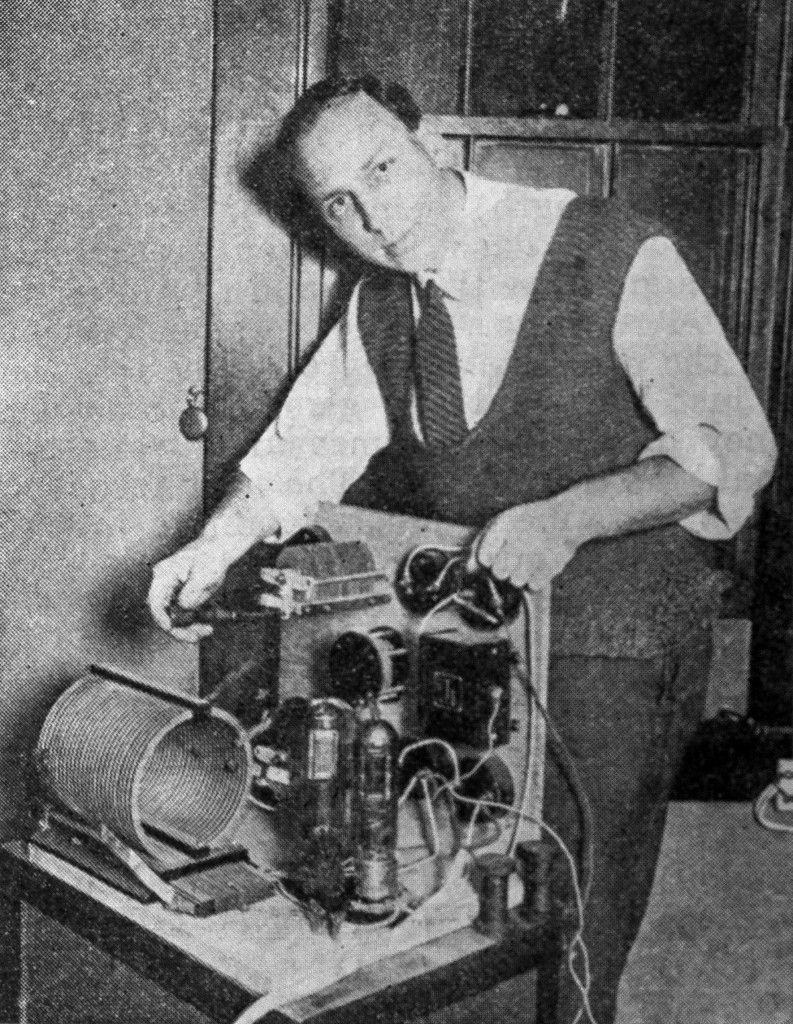

After acknowledging Deloy’s messages, Schnell sent some of his own, including greetings to various French notables such as Pierre Corret, the president of the French Joint Transatlantic Committee. While this was going on, Reinartz called 8AB from 1XAM on 115 meters, and heard Deloy acknowledge and ask him to QRX (stand-by). 1XAM was Reinartz’s experimental station in South Manchester, Connecticut, specially licensed for operation on 100 meters.11

Warner also “exchanged compliments” with Deloy for a short time, then Schnell invited Deloy to send a message for WNP (the MacMillan arctic expedition) on behalf of French amateurs. Although Schnell missed some of it, Reinarz copied it solid and acknowledged receipt. He and 8AB then “chewed the rag” for a while.

John Reinartz with transmitter at 1XAM

“For years we have dreamed of this,” beamed Warner, “for over a year we have seen it coming; for weeks we have been sure that winter weather would see the thing accomplished. It has been done, fellows; we are actually in back-and-forth contact with Europe over our amateur sets.”

After successfully sending the WNP message to 1MO on his second attempt, Deloy developed some transmitter problems and had to sign off just before 12:30 a.m. The next night conditions were very poor, making a repeat performance impossible. The night after that, on Thanksgiving Day, 29 November 1923, 1XAM made a short contact but could not copy 8AB reliably because of interference from KDKA’s “short concert wave” on 103 meters. On the thirtieth, 1MO was hearing 8AB quite loudly but could not copy what he was sending due to heavy static and QRM generated by local receivers! Four other amateurs reported hearing him, too.

More significantly than just being a record for 100-meter work, some amateurs began to recognize that operating on that shorter wavelength, rather than being more of a challenge, may have actually been what made it all possible. All three stations in this first set of QSOs were transmitting using the same Reinartz-modified Hartley oscillator, 8AB’s being powered by 25-cycle unrectified AC, which made it copyable using a non-oscillating detector. And the Connecticut pair both ran 500-watt transmitters with some degree of rectification on the plates. All receivers were based on regenerative Reinartz tuners: a Grebe at 1XAM, and a version at 1MO that was, as described by Warner, “at best a pile of junk” (a friendly jab at Schnell).

The point of all this was that there was nothing remarkable or special about any of the equipment except for the fact that the contacts were all made with it tuned to very short wavelengths. Warner concluded that, “the accomplishment is merely a demonstration, more effective than all of our talk, of the efficacy of the shorter waves.”

He then admitted that it would be “hard to explain to you fellows, we know, how an A.R.R.L. officer happened to win the Brown Derby offered by the Editor of QST as a trophy to the first ham to work to Europe. We hear agonized yells of ‘Collusion!’ We’re helpless, tho. Schnell vowed his determination to win the lid, he got busy and did it—and there’s nothing else to do, he has won it. (Jealous of our high British hat, we think, and wanted something to wear himself. Hi!).”

For his part in the achievement, Leon Deloy was later made a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur, or Knight of the Legion of Honor,12 the fifth degree of France’s highest decoration, first established by Napoleon Bonaparte.13

Testifying before the US Senate seven years later, Maxim described the event to try to convey the excitement of each new achievement in amateur radio:14

It is difficult to explain the thrill that accompanies an experience such as this. It is sublime and carries with it a sort of uplift that makes us better and deeper-thinking men. The precision of it all, the picture of the Frenchman sitting in his little den in France, waiting for the precise second to come around, hand on key, the Americans sitting in their little shack in a little street in New England, silently listening and watching the time, the miles and miles of lonely black ocean over which the little electro-magnetic oscillations must travel, are utterly compelling to us amateurs.

de W2PA

- Kenneth B. Warner, “Two-Way Tests with Europe,” QST, March 1923, 13. ↩

- “French Work on 45 Meters,” Radio Communication by the Amateurs, QST, October 1923, 50. ↩

- S. Kruse, “Exploring 100 Meters,” QST, March 1923, 12. ↩

- Calls Heard, QST, May 1923, 75. ↩

- F. H. Schnell, “The Fourth Transatlantic Tests,” QST, December 1923, 9. ↩

- Equivalent to nearly $50,000 in 2013. ↩

- Kenneth B. Warner, “Achievement,” Editorial, QST, January 1924, 7. ↩

- Kenneth B. Warner, “Be a Sport!,” Editorial, QST, December 1923, 7. ↩

- Leon DeLoy, “My Impressions of American Amateur Radio,” QST, December 1923, 17. ↩

- Kenneth B. Warner, The Editor’s Mill, QST, December 1933, 7. ↩

- Kenneth B. Warner, “Transatlantic Amateur Communication Accomplished!,” QST, January 1924, 9. ↩

- Clinton B. DeSoto, 200 Meters and Down, The American Radio Relay League, Inc., 1936, 97. ↩

- It had also been awarded to Edwin Armstrong in 1919. ↩

- “President Maxim Testifies at Washington,” QST, April 1930, 29. ↩