As 1916 drew to a close, Maxim made a plea to organize what might be the first round-trip relay across the country.1 The February Washington’s Birthday test had demonstrated relaying a message to the entire country broadcast-style, beginning in the Midwest. This one would be more difficult: a message originated on the East Coast would be relayed across the country, arrive at a West Coast station where a reply would be sent, which would then be relayed back to the origin, twice spanning the continent in a single relaying test—perhaps all in one night. Maxim compared it to the first telephone call and the first coast-to-coast automobile trip.2 Actually, he was not certain it hadn’t already been done, but no record of one had yet surfaced, only rumors. Since reports of successful contacts along many individual parts of the path had become common, he reasoned, it should be possible to stitch them all together.

Noting the rapid progress in radio technology, Maxim wrote, “Things are being done nightly right now, which were impossible this time last year. What is coming by this time next year, no man is bold enough to guess, for in no art being practiced today is advance so rapid as in amateur wireless telegraphy.” He had already taken the matter up with the trunk line managers and would be publishing a plan in the next issue of QST.

But an attempt at a transcontinental relay happened before any plan made it into print,3 “As a record for future generations to smile over, we herewith print,” that an attempt was made on 4 January 4 1917, after detailed preparation. Newspapers, in Hartford and Hoquaim, Washington, were set to exchange a previously arranged question and answer that had been kept secret—Hartford would do the asking. Maxim at 1ZM was to start the exchange with Henry W. Blagen, 7DJ, in Washington. Its failure was blamed primarily on excessive QRN combined with an unusual lack of propagation between the Midwest (8NH, 9ZN and others) and the Northeast (2ABG, 2AGJ). Personal accounts attested to horrible conditions and severe weather. Furthermore, 7ZC in Montana reported that the western leg had been in flux anyway, with his critical relay station having been notified of the test only one day in advance, and another, 7ZH, in the middle of a move. They would try again.

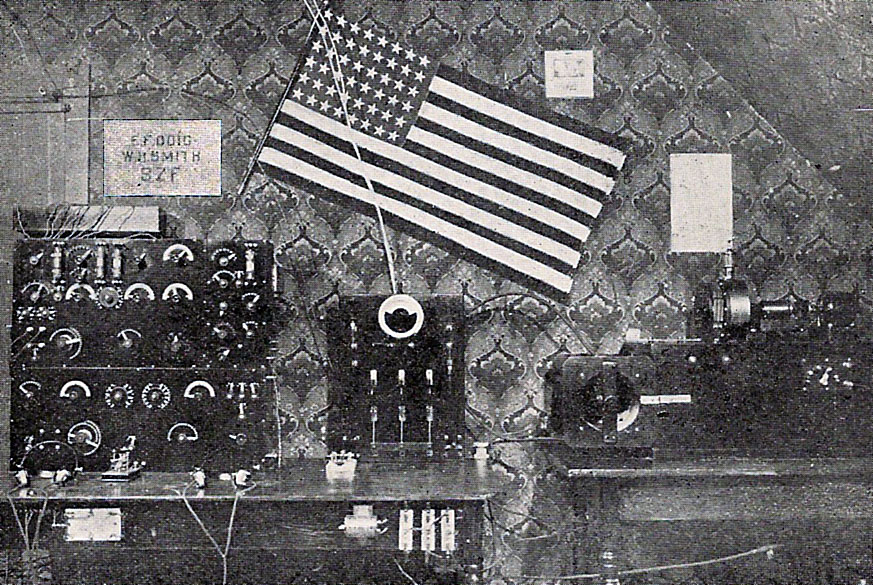

9ZF

Less than two weeks later on 17 January—success! The first trans-continental one-way message relay occurred; three of them in fact, all originated from the Seefred brothers sent to ARRL Headquarters.4 The messages traveled via five hops: Seefred Brothers, 6EA, Los Angeles, California; E. A. Smith, 9ZF, Denver, Colorado; W. P. Corwin, 9ABD, Jefferson City, Missouri; K. Hewett, 2AGJ, Albany, New York; H. P. Maxim, 1ZM, Hartford, Connecticut—the longest hop being 1040 miles from Jefferson City to Albany. But 9ZF was acknowledged as having been pivotal since his station was the only link along his segment; the others all had parallel routes available. The relays continued through early February—in all, 21 messages were passed, every one of which went through 9ZF. This was not along an already established trunk line but, no matter: It now was designated as such and assigned to Mathews and his northern line.

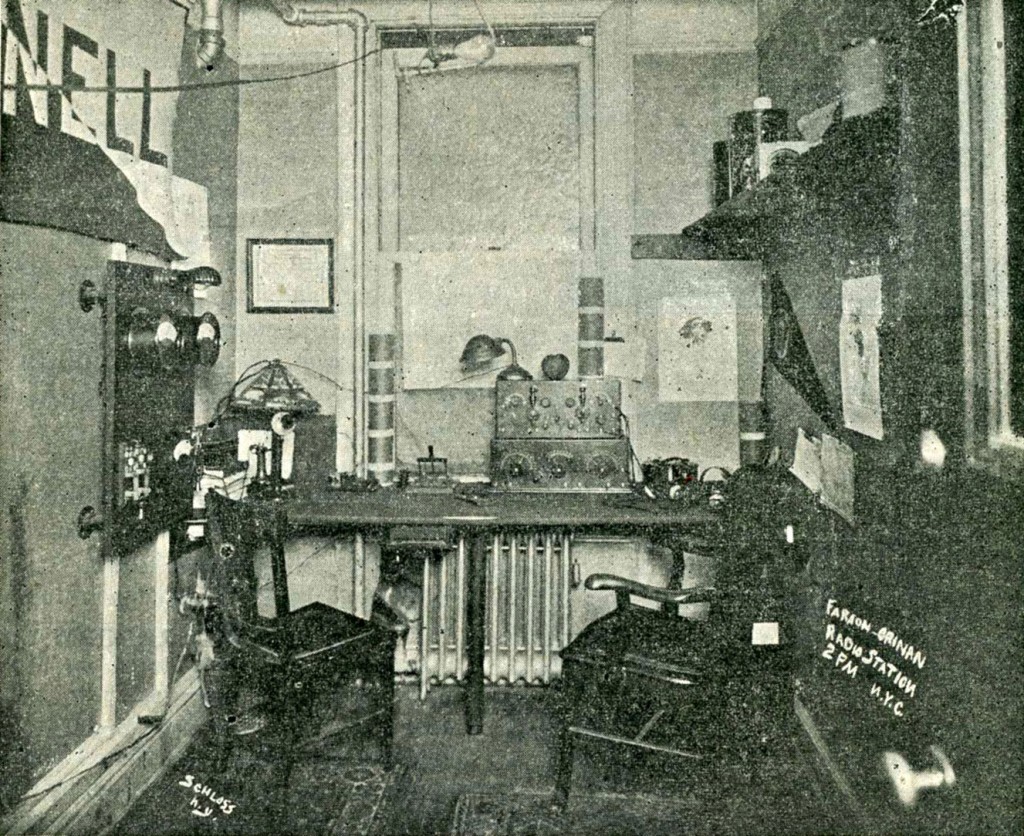

Then, a couple of weeks later in the early morning of 6 February, a round trip relay was completed all in one night.5 “The job was done by 2PM, Faraon & Grinan in New York City, 8JZ, Alfred J. Manning, Cleveland Ohio; 9ABD, Willis P. Corwin, Jefferson City, Mo., 9ZF, W. H. Smith, Denver, Col., and 6EA, Seefred Bros., Los Angeles, Cal.” The QST editorial proclaimed, “They are the big bugs of Amateur wireless.”

Star Station 2PM in New York City

2PM was highlighted later that year as the “Star of the Second District.” The “most efficient” station in the east, they claimed to be the only one in the heart of New York City engaged in long distance work.6 Urban QRM and QRN normally drowned out weak signals.

Previously, eastern-originated messages had reached the West Coast in 3 days. Even earlier, they had gotten across on “QST signals,” that is, ones that were neither pre-arranged nor in some cases even acknowledged. This round trip message left 2PM (the call sign, not the time) at 1:40 a.m. and the response came back at 3:00 a.m., making the round trip in 1 hour, 20 minutes. ARRL HQ knew of fifty additional messages that had traveled along the trunk lines across the country. The editor correctly predicted that this new record would not last long.

Maxim sent a radiogram to the New York Times on March 6, announcing that the League was now handling round-trip coast-to-coast messages in less than two hours.7 A reporter interviewed J. O. Smith, who was quoted emphasizing the volunteer nature of amateur radio, saying, “They are all amateurs, just ‘bugs’ on wireless telegraphy who gave up their spare hours and their money to the hobby.”

Smith, the new manager of trunk lines C and D (Hebert having recently become ARRL general manager) commented, “This great stride forward in amateur relay work over one year ago, undoubtedly due to the regenerative receiving sets now in use and the greater efficiency obtaining in amateur transmitting sets in general, tells its own story.”

The story would soon be rudely interrupted.

![]()

de W2PA

- Hiram Percy Maxim, “The First Trans-continental Relay,” QST, December 1916, 10. ↩

- The first one was accomplished in 1903 by Horatio Nelson Jackson, a physician, and Sewall K. Crocker, a mechanic, who drove from San Francisco to New York in a little over one month. ↩

- A. C. Campbell, “First Trans-continental Relay Fails,” QST, February 1917, 40. ↩

- “Trans-continental Traffic Begins,” QST, April 1917, 18. ↩

- “The Transcontinental Record,” QST, April 1917, 17. ↩

- “The Star of the Second District,” QST, August 1917, 13. ↩

- “Amateur Wireless Crosses Continent,” The New York Times, March 8, 1917. ↩