As amateur stations fell silent, the airwaves continued to carry commercial and military signals, many from the fingertips of former radio amateurs. But despite their contributions there were some in government who still sought to limit or eliminate the use of wireless by private individuals.

As the battles ceased in Europe, amateur radio came under renewed attack at home. Bills introduced in both houses of Congress shortly after the armistice sought to turn control of all use of radio over to the Secretary of the Navy who with others had been trying to restructure radio law along these lines for some time. The previous spring, Maxim had personally appealed to the sponsors of one bill, successfully obtaining an exemption for amateur radio stations. And that summer there was yet another new bill pertaining to commercial radio, with amateur operation again specifically exempt. Present at a hearing for the bill, the League had accepted at face value the Navy’s assertion that they did not want to kill amateur radio. But now at the war’s end, their attitude had clearly changed; this new bill would indeed have had just that effect. The League did not protest the Navy ownership issue, only the specific provision eliminating amateur radio.

This time, with QST out of print, the ARRL sent out “Little Blue Cards” to all licensed amateurs alerting them to the new threat and asking for support. To cover the cases where an amateur was away from home, deployed with the military—there were very many of those—the cards were addressed to “any member of the family” of the amateur. The response may have exceeded even Maxim’s expectations. Letters and telegrams poured into Washington in opposition to the bills, sent by amateurs and their families including those of hams killed in the war. The League’s Board of Direction sent Maxim to testify before a hearing of the Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries, the body in charge of the House bill. Several prominent clubs also attended to speak in opposition. The bill never made it out of committee.

Years later DeSoto took note of what an “extraordinary thing” this really was.1 A well-backed bill had been defeated at a time when there were no amateurs on the air and radio as a hobby no longer existed. This stood in stark contrast with what happened in 1912 when there were thousands of individuals involved in radio and yet a law was passed imposing severe restrictions on them. The difference lay in strong organization on a nationwide scale.

With $33 in the treasury, the ARRL board began to meet again in the spring of 1919 and got to work reorganizing. That included drawing up a new constitution, electing officers and putting a plan in place to finance starting up again.

The abrupt end of amateur operations had been reflected in kind by the equally abrupt end of QST a few months later, a victim of expired subscriptions and cancelled contracts with advertisers. The magazine’s own success in recruiting amateurs to enlist in the military had ironically resulted in a lack of amateurs left to support it. All ARRL memberships expired during the war along with all amateur licenses.

At a meeting in New York on 29 March, a group including Maxim, Tuska, Hebert, and eight others decided to donate the $100 necessary to publish a “midget” issue of QST as a first step in building support to get the journal back into its pre-war form. That issue emerged as The American Radio Relay League Special Bulletin—only eight pages—with a stated purpose of “Getting Together Again.” It was folded in thirds like a business letter, closed with a seal and mailed with a one-cent stamp.

At a meeting in New York on 29 March, a group including Maxim, Tuska, Hebert, and eight others decided to donate the $100 necessary to publish a “midget” issue of QST as a first step in building support to get the journal back into its pre-war form. That issue emerged as The American Radio Relay League Special Bulletin—only eight pages—with a stated purpose of “Getting Together Again.” It was folded in thirds like a business letter, closed with a seal and mailed with a one-cent stamp.

One of those eight pages was written by The Old Man. Surprised by a telegram from the editor, he wondered if it could mean the end of these “wirelessless days” was coming at last. His code was rusty, his grasp of technical details was rusty. And how would his equipment have fared being in storage all this time? Everything was “Rotten Rusty.”2

Maxim, as himself, explained how the restart would be paid for. With the war over, the Board of Direction anticipated an influx of amateurs in much greater numbers than before it started, all having been trained in radio by the government, a dividend of their earlier recruiting effort. The board therefore set a goal to not simply resume publication but also set up an office with a paid secretary. The directors estimated that $7,5003 would be needed to get it all in place, including the purchase of QST magazine from Tuska, its present owner, for $4,700, which in turn included printing charges left unpaid since just before the war shut everyone down. The ARRL would raise the funds by selling “regular bonds” to members, ARRL Bonds that paid 5% interest and would be retired after two years. Voted on by the Board at its March 29 meeting, $2,500 had already been raised by the time of the bulletin’s printing.

On Saturday, 12 April, to the delight of amateurs, the Navy unexpectedly announced the lifting of the ban on receiving effective 15 April.4 ARRL HQ was immediately flooded with telegrams. The editors noted that “The news caused an electrical impulse to instantly pervade the entire country. It was like the news of the Armistice. It seemed to fill the breasts of thousands of us with a wireless enthusiasm that had not been experienced for many a long day.” Spring had sprung and the wireless bugs were coming out of hibernation.

QST officially returned in June. Billed as the “Reopening Number,” it still had no cover. In its main headline Maxim announced that the ban on receiving had been lifted and that the Navy indicated that transmitting would be allowed as soon as the president declared the end of the Great World War5. The ARRL extended the “hand of good fellowship” to all amateurs, member or not.

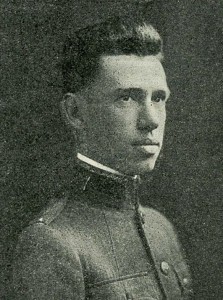

Kenneth B. Warner in uniform during the war.

New editor and General Manager Kenneth Warner wrote the editorial that month and added his own plea for restart funding. In doing so, he stated that QST’s purpose and its value to amateurs was “… to foregather and improve their knowledge and have a hearty laugh,” officially asserting the importance of humor, and to serve an organization that was “of amateurs, for amateurs, and by amateurs,” possibly coining for the first time the phrase that later became an ARRL motto.6 Then this:

Somehow or other, we wireless bugs seem to have a better fraternal spirit and a more highly developed sense of humor than other mortals, as our A.R.R.L. history has shown in the past. Let us keep it up, and let every fellow who has anything to loan from a dollar up come across with it and help the game along.

The Old Man obviously was in agreement. In the same issue he described the frantic rush to set up equipment again, largely starting from scratch, causing a shortage of supplies such as wire and soldering materials.7 He wrote about the trials of new antennas, masts and ground systems, finding the whole process pretty rotten as usual.

Before the war and its shutdown, he had written about the prevalence of QRM while trying to relay messages, mentioning the “little boys” yet again—and complained about bad operating that he’d overheard, citing several examples. He puzzled about one particular message he copied that had been especially garbled by the operator’s bad sending:

Listen to this: – ‘Yes yes jst wyd glucky wait a rnt muddy wouff hong bliftsyf monkey motor.’ We assume from this msg that Glucky is being asked to wait a minute while Blifsky seeks a wouff hong with which to wallop a monkey the next time the latter faces toward the motor. I do not think I know just exactly what a wouff hong is.

Quite fond of nonsense words like “rettysnitch” and “ugerumpf,” this was his first reference to a wouff hong in QST8—a particular term that would live on in ARRL and amateur radio lore. At no point did he suggest using a wouff hong (whatever it might be) on a person.

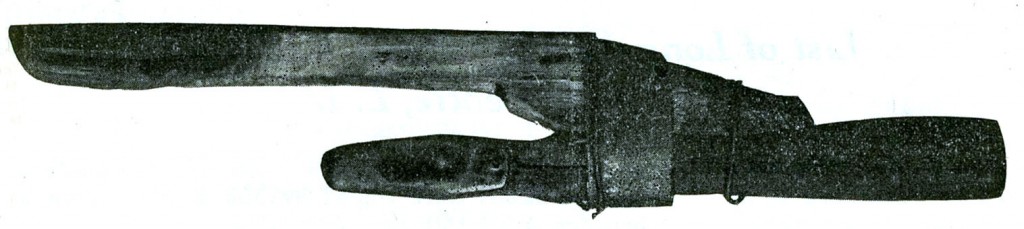

Now that the war was over, The Old Man judged the whole starting-up process to be quite rotten; clearly it was time to revisit the wouff hong idea. No longer simply a string of letters in a garbled message, it took on a new life of its own as a solid object. He closed his article writing that he had sent the ARRL an actual wouff hong which he found among his junk. In his column, Warner wrote of being shocked upon opening the package from T.O.M. to see the “authoritative specimen.” Displayed at the Board meeting, no one seemed to know quite how it was intended to be used, though The Old Man’s stories told of its use on spark coils and QRM creators in the Midwest where he lived. The editors invited the membership to comment and offer any insight they might have about it. Meanwhile, the nasty implement was framed and hung on the wall at headquarters in Hartford9 for all to see, and pictured that month in QST.

Wouff hong – the definitive specimen

While the ARRL treasury had yet to reach a sufficient level for normal operation, humor was in abundant supply.

In the Operating Department J. O. Smith as Traffic Manager, a new position, recapped the current structure of division managers. This new section of QST was established to cover on-air activities each month, primarily in traffic handling. Stations were directed to keep a log to accurately report to superintendents each month. Smith pointed out that once transmitting was again permitted, all operating and station licenses will have expired, requiring new licenses to be issued.

He reminded everyone that a transmitting station could not be operated without a license under the current law,10 something still not obvious to everyone.

In one of the biggest post-war changes, many amateurs were preparing to operate by installing equipment for transmitting undamped (later called continuous wave or CW) signals. This would certainly make issues such as decrement irrelevant, and would also help solve the QRM problem.

The pre-war trunk line system was no longer in place. Though many active relayers were still in the Navy or Army, several had already returned and volunteered as superintendents. Each division office called for stations to register interest so that the relay system could be reconstituted. A “Personal Notes” section of QST summarized where some well known operators now were, having moved or taken new jobs during or after the war.11 At the end is a framed note from the mother of William Woodcock, 8SK, telling of her son’s death from pneumonia while serving at the Great Lakes Training Center.12 She enclosed a donation in memory of him.

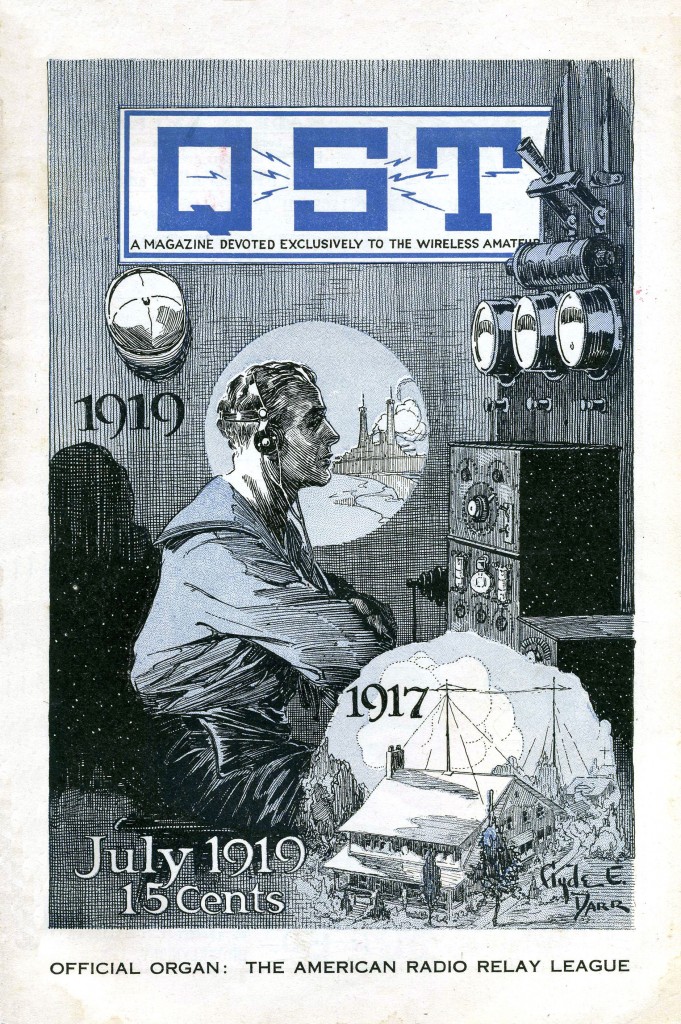

Finally, Warner noted that “QST will be issued regularly from now on.” As if to corroborate, the magazine was back to its familiar format with 36 pages for July and reported that the ARRL was halfway to its financing objective. The cover art by Clyde E. Darr, 8ZZ, showed an operator in a Navy uniform sitting at the controls of a station clearly not his own—the only on-air reality for hams in 1919. By contrast in a small inset drawing, a house with an aerial appears—the home and station he left in 1917. Hams’ lives had changed dramatically in just two years and it all stemmed from their passion for wireless and its relevance to the war effort.

de W2PA

- Clinton B. DeSoto, “200 Meters and Down,” The American Radio Relay League, Inc., 1936, 55. ↩

- The Old Man, “Rotten Rusty,” QST, April 1919 (“Midget” issue of QST), 5. ↩

- About $100,000 in 2013. ↩

- “Receiving Permitted,” Editorial, QST, June 1919, 14. ↩

- ibid ↩

- “A.R.R.L. Loan,” Editorial, QST, June 1919, 13. ↩

- The Old Man, “Rotten Starting,” QST, June 1919, 8. ↩

- The Old Man, “Rotten QRM,” QST, January 1917, 8. ↩

- Still at HQ, it hangs in a glass case in Newington today. ↩

- J. O. Smith, The Operating Department, QST, June 1919, 17. ↩

- “Personal Notes (on staff),” QST, June 1919, 22. ↩

- “In Memory of William D. Woodcock, Ex-8SK, Silent Key,” QST, June 1919, 25. ↩