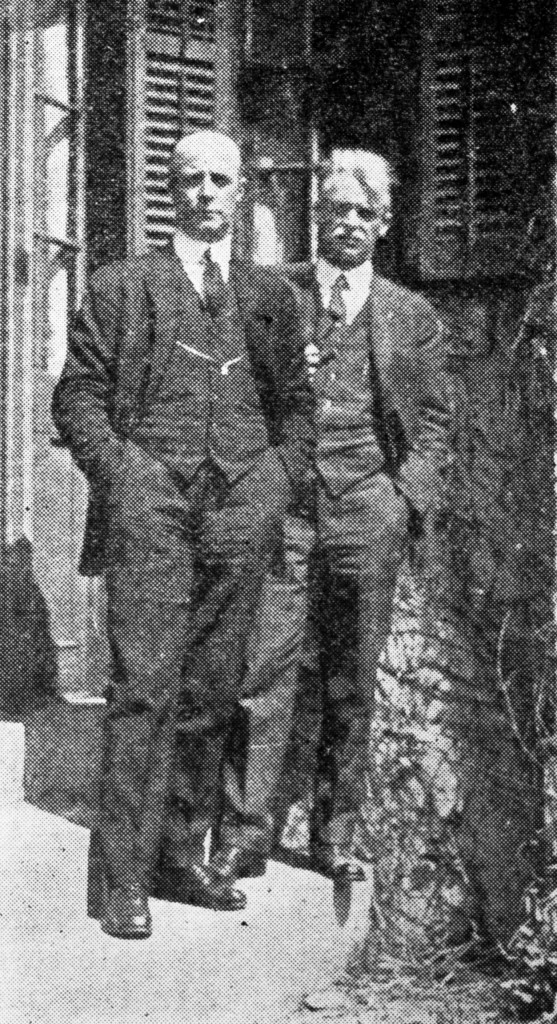

Donald MacMillan with Hiram Percy Maxim at Maxim’s home in Hartford, Conn.

Donald B. MacMillan, an experienced arctic explorer and geologist, visited Hartford in early 1923 to discuss amateur radio with Hiram Percy Maxim.1

Among his various scientific investigations, MacMillan was planning to study the aurora borealis. No one yet understood what the aurora was, but he had experienced it on previous trips and noticed that he could hear long wave radio signals through it. On his next expedition, besides photographing the aurora, he wanted to experiment with shortwave radio signals to see whether they were affected by it. And, perhaps influenced by the broadcasting boom, he intended to use radio for more than scientific work alone. He believed it might also help combat the loneliness of a long arctic winter camp and its damaging effects on crew morale. Just hearing voices and music from the civilized world would be a big boost; two-way contact would be huge.

MacMillan was in town to ask Maxim for help from the ARRL during the expedition and to select an amateur radio operator to join his crew.

The plan began to take shape almost immediately. The expedition would be on the air beginning on 20 June, identifying itself with the call sign WNP (for wireless north pole). Although the shipboard station was licensed to use any wavelength its operator chose, they planned to operate between 200 and 300 meters, still considered shortwave.

After considering a list of candidates to accompany the expedition, the ARRL Board chose Donald H. Mix, 1TS, of Bristol, Connecticut, who was then interviewed by MacMillan and accepted as a member of his crew.2 A longtime major contributor to the Calls Heard section in QST, Mix was well known as a skilled operator and active League member. Among his many accomplishments, he had earned the distinction of having copied the most West Coast stations of any other amateur in New England. A graduate of Bristol High School, Mix was employed by the C. D. Tuska Company in Hartford—ARRL co-founder Clarence Tuska’s company—as head of the assembly department.3 It’s therefore no wonder that when he agreed to go on the trip, his employment situation would not be an issue.

At age twenty-one, never before having been on a sea voyage of any kind, much less one to the arctic, Mix would confront new challenges daily. And as an amateur radio operator he would have to deal with operating conditions never before experienced by anyone—working through perpetual daylight for the first few weeks and sometimes through aurora. Back home, the League’s job would be to regularly make contact with WNP and relay news stories sent by Mix to a syndicate of seventy newspapers called the North American Newspaper Alliance (NANA).

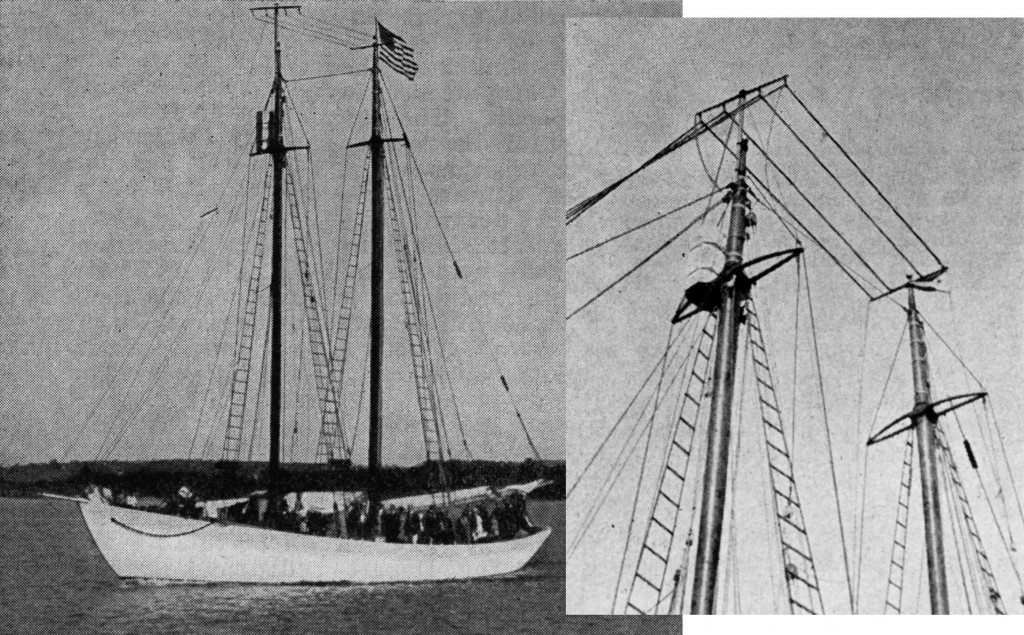

The Bowdoin

MacMillan’s schooner, the eighty-foot Bowdoin, named after Bowdoin College, his alma mater, could carry two thousand gallons of fuel, giving it the longest range under power of any sailing vessel in the world—about one thousand miles. The ship would navigate a course north along the western shore of Greenland and across Baffin Bay to anchor at Flagler Bay in late August, where it would spend the next nine months frozen in the arctic winter ice. At 79° north latitude, the location was about 540 miles northeast of the magnetic pole, and 700 miles from the geographic pole. MacMillan had chosen this spot to support his scientific mission to study geomagnetic effects and local wildlife. If all went as planned, the following summer thaw would permit their return by September 1924.

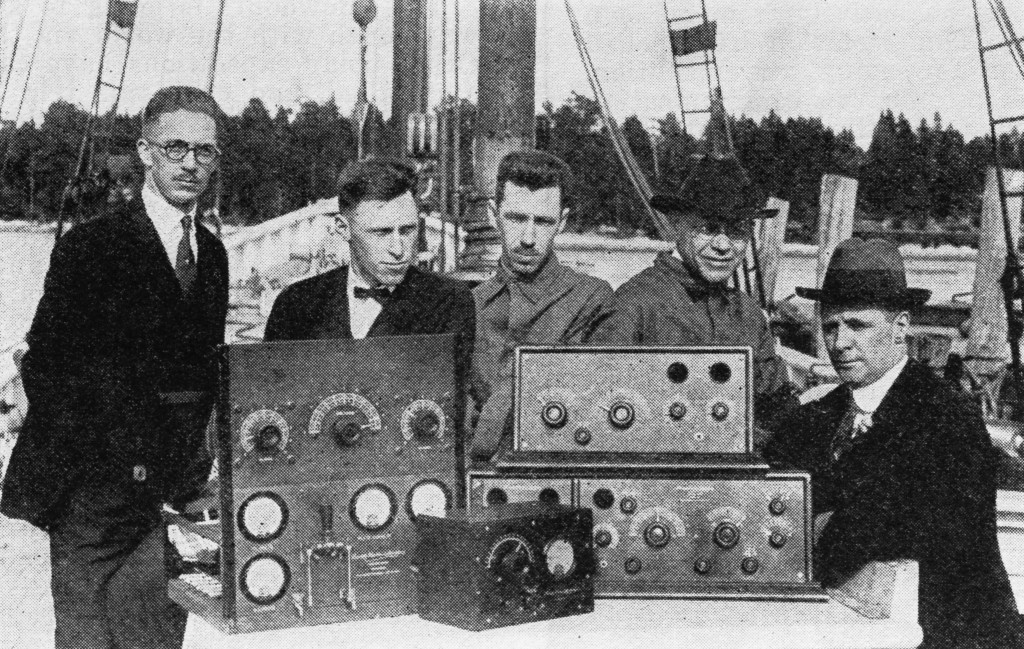

The expedition’s radio equipment was designed by M. B. West, 9BA, well known before the war as 8AEZ. West had resigned his civilian job with the Navy to join the Chicago Radio Lab, recently renamed Zenith.4 He visited the Bowdoin at its dock in Southport, Maine, to take measurements, acting as tailor for its new radio outfit. The equipment was then hand-assembled by West and other amateurs at Zenith, the company founded by R. H. G. Mathews whose call sign, 9ZN, had inspired its new name. “It is a ham party,” observed ARRL Secretary Warner, especially with the rest of the ARRL to communicate with. Although other polar expeditions had carried radio equipment, none had yet succeeded in using it effectively. This one would be different.

WNP was equipped with a Zenith model 1-R receiver covering shortwaves from 150 to 850 meters, and a longwave set for receiving naval stations NAA and NSS.5 Its transmitter was a two-tube circuit, running 100 watts, designed to tune into antennas that were shorter than normal, limited by the size of the ship. All units were built as proper furniture, with panels of “mahogonite Radion” and cabinets of “piano-finished mahogany.”

Zenith station equipment aboard the Bowdoin. Left to right are Fred Schnell, Don Mix, Kenneth Warner, M. B. West, and Donald MacMillan.

The station’s daisy-chain power supply consisted of a 500-watt Telefunken 500-cycle alternator, which was driven by a DC motor, which drew current from the ship’s 160-ampere-hour automotive batteries, which were kept charged by a pair of 350-watt Delco light plants, a kind of fuel-powered generator used at the time in rural areas for lighting.

In addition, the plate voltage for the vacuum tubes was supplied by a separate set of batteries. The Burgess Battery Company of Madison, Wisconsin, plucked their best 1,000 cells from a 10,000-unit manufacturing run and delivered them to the expedition in special waterproof packages, all free of charge. These would last 18 months—longer than would be necessary. But as a contingency, Burgess also supplied tools, parts, and chemicals for them to construct new batteries from scratch to last an additional two years.

The radio equipment was first tested all together in Chicago where the engineers found they could easily work several distant stations including 1AW in Connecticut and 6KA in California, all on a short antenna. West and the Zenith crew then installed it on board the Bowdoin on 31 May, and were on the air signing WNP. The company also stocked the ship with enough spare parts to completely replace the receivers and most of the parts in the transmitter and power plant should that become necessary.

Mix planned to operate on 185, 220, and 300 meters, with the primary wavelength being 220. He would be on the air every night, closely rationing operating time to conserve fuel. MacMillan intended to send weekly reports which the ARRL would then relay to the news alliance. Mix would also log all calls he heard and include the list in his reports. Amateurs who received reports were instructed to mail them to a NANA member newspaper immediately, and then send a copy to ARRL. Messages marked URGENT (used only for emergencies) were to be telephoned or telegraphed to a NANA newspaper immediately.

As the Bowdoin set sail on 23 June for her 14-month voyage, Maxim was present to see the expedition off at its dock in Wiscasset, Maine.6 Shortly afterwards, Vermilya, 1ZE, was assigned to receive the first news dispatch for the newspapers. Despite bad weather in July, a half dozen amateurs worked WNP and perhaps twice that many heard its signals in the first couple of months.7 But communications worsened and then remained poor once they reached far enough north to experience the arctic all-day summer sun in early August. Mix could hear and even log stations but not work them. Even powerful NSS was not copyable due to weak signals and QRM from European commercial stations.8 Eventually the change of seasons caught up with and passed the Bowdoin as it proceeded north so that the sun once again set, spending about three hours below the horizon by late August.

Though two-way contacts continued only sporadically, the ones between WNP and 1ANA in Chatham, Massachusetts, were most impressive. They spanned 2,500 miles when the expedition was within 50 miles of its destination, with mid-summer daylight conditions presiding over a major portion of the route.9

R. B. Bourne, 1ANA, a “receiving engineer” at RCA, handled most of the reports from the MacMillan expedition during its first few months.10 He used an unconventional antenna: a tilted inverted-L consisting of a 45-foot section angling upwards and away from his 100-foot steel tower, connected to a 70-foot top section angling up in the opposite direction where it terminated into an insulator at the top of the tower, which was connected to station ground. In effect, this made it a huge single-turn triangular loop with an insulated break at the top, which acted like a condenser in series.

The Bowdoin with aerial. Aerial closeup at right.

The transmitter, located in a small, windowless beach hut just big enough for the equipment, was a single 50-watt tube driving the antenna on 185 meters. He used a Reinartz receiver that was modified to be capable of tuning down to 75 meters. Its antenna was simply a 60-foot-long wire 30 feet in the air. From the receiving station located several hundred feet away, the transmitter was controlled by a single wire with ground return which drove two relays. This permitted a kind of break-in operation that was not at all what we would call QSK today. A momentary tap of the key threw a polarized relay, which applied plate and filament voltage to the transmitter. The plate voltage did not appear immediately since a high voltage vacuum tube rectifier was used and took time to warm-up. Once things were heated and ready, subsequent keying applied voltage to the primary of the plate supply transformer via the second relay. When transmission was over, a second key sent a reverse polarity voltage to the keying line, which then toggled the polarized relay off.

Persistence had paid off for “BO” at 1ANA, who did not have a particularly powerful or elaborate station, but more importantly was “a good operator who has the patience to sit and listen,” wrote ARRL Traffic Manager Fred Schnell. He believed that this testimonial to operator skill would inspire others to get on the air and listen more carefully as winter approached and conditions gradually improved.

In Chicago, Mathews announced that a prize—a duplicate of the receiver installed on the Bowdoin—awaited the next US or Canadian amateur to take an official MacMillan message. Schnell remarked that, “1ANA already has made room in his shack for this outfit.” Unfortunately, Bourne was taken out of contention, forced to shut down shortly after his initial contacts, when his employer, RCA, transferred him to their Marion, Massachusetts, station.

Although very spotty contact continued as fall approached, Mix began to hear West Coast stations frequently. Finally, just before midnight on 7 September, 7DC made brief contact but signal strength and conditions were so poor he could not even get the “all’s well” message from Mix. Others were listening too.

Jack Barnsley, Canadian 9BP at Prince Rupert, British Columbia, happened to hear WNP trying without success to reestablish contact with 7DC that night. After waiting a few minutes for a reply and not hearing one, he called WNP and was thrilled a half-minute later when Mix replied that he was “VY QSA,” meaning perfectly readable.

Barnsley copied the first NANA news bulletin from WNP after the expedition set up camp, and was then in regular contact for the rest of the year.11 12 Having kept detailed logs and traffic count by the word, Mix later reported that of the 16,000 total words he’d sent, fully half had gone through 9BP.8 “On one night he worked nearly two hours copying thirty words under conditions where an ordinary operator would have given up,” wrote Mix.

Barnsley’s anchor station, 9BP, had also been the westernmost participant in the Canadian transcons (transcontinental message relays).14 He used two 50-watt tubes with 1,500 volts on the plates for a transmitter, and, for receiving, a Paragon model RA-10 regenerative tuner and model DA two-stage audio amplifier, similar to Godley’s station in Ardrossan. This was fed by an inverted-L aerial of conventional cage design having a vertical section 65 feet high and a 75-foot horizontal run, with a 12-wire counterpoise ground system strung below.15Jack Barnsley would accept the CRL Zenith receiving setup in reward for his work with WNP.

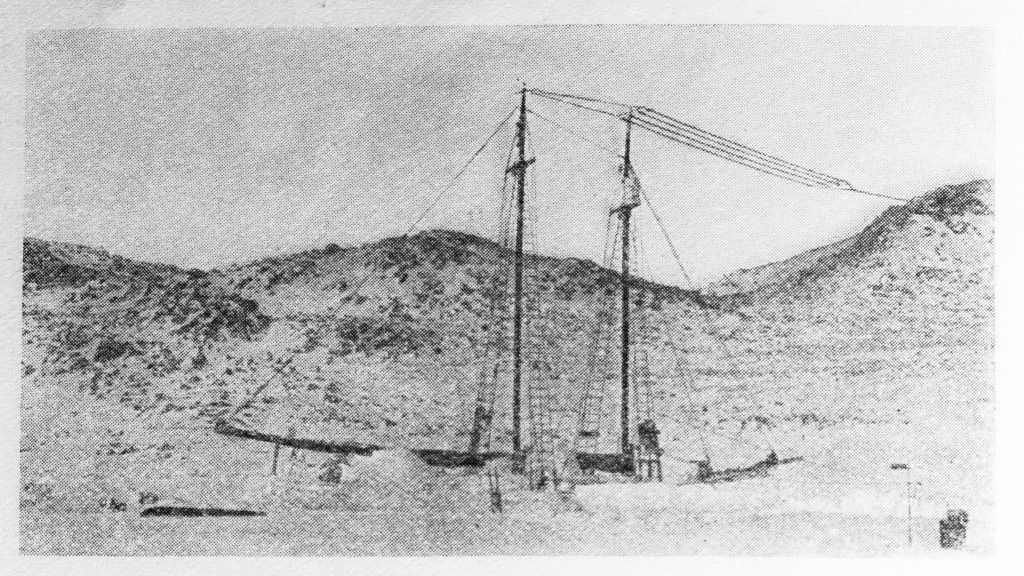

The Bowdoin during winter camp, outboard aerial in place.

The equinox came and went and the nights grew unusually long. By mid-November 1923 the Bowdoin was frozen in place at temperatures well below zero Fahrenheit, and the sun had not been seen since late October—an uncomfortable environment for radio operators but ideal for radio. WNP was now being copied mostly by West Coast stations, only a few elsewhere and none on the East Coast any longer. Besides receiving the news dispatches, 9BP was also passing along traffic to families of the expedition’s crew and sending back news from home.

With improving on-air conditions during November, twenty amateurs worked WNP in fifty-one QSOs.16 It was the best traffic month of the expedition according to Mix, as 9BP continued to handle nearly all of their message traffic including the press reports. A new two-way distance record was set in a 15-minute QSO between WNP and R. Smith, 6CEU, of Hilo, Hawaii, who was transmitting with three 5-watt tubes. Mix wrote that he nearly fainted when he heard Smith answer his CQ. They continued to work each other right through the winter.

Mix strung new antenna wires from the ship’s mast to some nearby hills, a relief from the confines of the ship’s dimensions, which had limited the antenna’s length. The Zenith equipment had been performing very reliably—no tubes had been changed since leaving Maine. At this point he was getting news directly from six amateur stations plus European commercial stations POZ and GBL, and reported hearing music from a station in Glasgow, the only European broadcaster that he could identify. As the winter progressed he began to hear many more North American broadcasters. The crew was especially surprised one night to “hear CFCN call out ‘Hello WNP somewhere in the Arctic. Hope you are getting this.’”

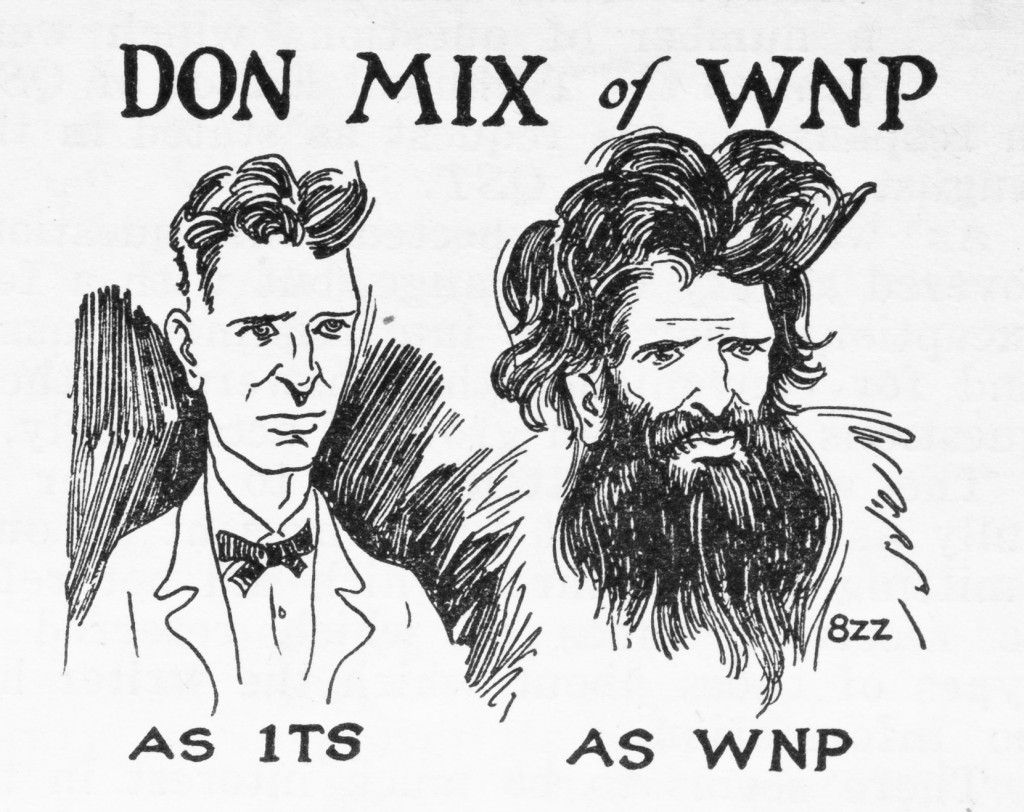

Mix, before and after, in a cartoon by Clyde Darr, 8ZZ

A cartoon drawn by frequent QST cover artist Clyde Darr, 8ZZ, depicted his conception of Don Mix’s transformation from bow-tied and suited, clean-cut New Englander to whiskered and wild-haired arctic explorer fitted in fur. Born in 1879, Darr had grown up in radio closely paralleling Vermilya’s example, passing through the neighborhood telegraph, spark coil, and transformer stages to become a first class CW operator as 8AJD and 8CB.17 After qualifying for a special license and receiving his prized 8ZZ call sign, his became the first station in Detroit to broadcast music. As president of the Detroit Radio Association, member of the ARRL board, and Central Division assistant manager, Darr was well known for his work both on and off the air.

On 22 December 1923 President Coolidge sent a holiday greeting to the MacMillan expedition via the RCA station in Washington, D.C.18 Not having a commercial station in the arctic, RCA then telephoned ARRL headquarters to ask whether the League could convey the message. So QST Technical Editor Kruse began trying to send it from his home station in Hartford that same night. But conditions were particularly poor with loud electrical power line noise pervading the air. He was therefore pleasantly startled to hear Darr at 8ZZ “merrily chewing the rag” with Mix at WNP. Kruse called repeatedly but could not make contact. Exasperated, he turned for help from several other local stations who all tried to raise 8ZZ, only to hear Darr complain of the QRM, then abruptly sign off for bedtime, just missing his chance to deliver the president’s Christmas message in time!

The next night Kruse contacted two other Detroit area hams who went over to Darr’s house and woke him up to try again for WNP—but it was not to be. On 24 December 8ZZ finally got it relayed to Barnsley at anchor station 9BP who uncharacteristically could not raise WNP either. After trying for several additional nights he finally got through and passed the message on the evening of New Year’s Day 1924. The final reported routing path of the president’s message was 1HX–8ZZ–5GO–9BP–WNP. To speed things up, the reply message went via wire directly from Barnsley.

Propagation continued to mystify and amaze all involved, especially when WNP reception reports began arriving from New Zealand.

Unknown to the northern explorers, new radio territory was also being charted far south of 200 meters by explorers of another kind.

The MacMillan expedition is one of the most well documented and widely written about events in early amateur radio history. For additional reading see the articles by Dilks19 20 21 and the book by Bartlett.22 We will pick up WNP again here, later.

de W2PA

- J. K. Bolles, “Arctic Explorer to Communicate with Amateurs,” QST, June 1923, 9. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “Amateur Radio Shoves Off for the Pole,” QST, July 1923, 7. ↩

- Who’s Who in Amateur Wireless, QST, August 1923, 52. ↩

- Strays, QST, August 1922, 55. ↩

- S. Kruse, “Station WNP, on Board the ‘Bowdoin’,” QST, July 1923, 9. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “The Departure of ‘WNP’,” QST, August 1923, 16. ↩

- F. H. Schnell, “Have You Heard or Worked WNP?,” QST, September 1923, 14. ↩

- D. H. Mix, “My Radio Experience in the Far North,” QST, November 1924, 17. ↩

- “Wireless North Pole,” Editorial, QST, October 1923, 29. ↩

- Amateur Radio Stations, QST, November 1923, 57. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “West Coast Working ‘Bowdoin’, WNP,” QST, November 1923, 21. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “9BP Still Chief Contact with MacMillan,” QST, December 1923, 23. ↩

- D. H. Mix, “My Radio Experience in the Far North,” QST, November 1924, 17. ↩

- Amateur Radio Stations, QST, December 1923, 49. ↩

- Like the one used at 1BCG during the transatlantic tests, this is an above-ground network of wires that takes the place or augment an earth ground connection. ↩

- “Splendid Contact with the ‘Bowdoin’,” QST, January 1924, 28. ↩

- Who’s Who in Amateur Wireless, QST, August 1922, 48. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “Coolidge’s Holiday Greetings to MacMillan Travel Via Amateur Radio,” QST, February 1924, 29. ↩

- John Dilks, “Where in the World is the Bowdoin?,” QST, August 2008, 95. ↩

- John Dilks, “Wireless North Pole Christmas,” QST, December 2008, 94. ↩

- John Dilks, “Don Mix Returns Home,” QST, March 2010, 94. ↩

- Richard A. Bartlett, “The World of Ham Radio, 1901–1950,” McFarland and Company, Inc., 2006, 163. ↩