On the evening of 27 November 1923, a mother in Connecticut sent Thanksgiving greetings to her son who was a great distance away, via radio.1 She paid nothing for this service since her message was handled entirely by amateur radio operators. Impressively, it arrived only six minutes after she dictated it to a local ham on the telephone, traveling more than 6,000 miles to reach its addressee. Since her son happened to be aboard a ship that was frozen motionless in ice 700 miles from the North Pole, amateur radio was really the only way to convey such a greeting. Her message had traveled from Bristol, Connecticut via Catalina Island, California, to Etah, Greenland where the MacMillan expedition received it via its amateur radio station, WNP.

Don Mix’s mom had participated in setting a new relay record, albeit one that lasted for only a day. The following night, the same group was at it again. 1XAQ in Bristol sent a message to WNP via 6XAD on Catalina (a specially licensed 100-meter station owned by Lawrence Mott, 6ZW) and received an acknowledgement five minutes and six seconds after starting the message. This was now the longest three-station round-trip relay—12,300 miles—and the fastest, traveling at 2,412 miles per minute. (QST mistakenly printed it as miles per hour in the summary box—though fast for transportation, that would be quite slow for radio.) This three-station relay circuit operated fairly reliably for more than a week.

The morning before Mrs. Mix’s Thanksgiving message, another milestone was reached. Deloy at French 8AB sent a message addressed to WNP to 1XAM (John Reinarz’s experimental station) who telephoned it to 1HX who then passed it to 6XAD as before. But since WNP was not on the air at the time, 6XAD passed it along to Barnsley at Canadian 9BP who got it to WNP the following night. Though not a speed or distance record, it was the first four-country relay.

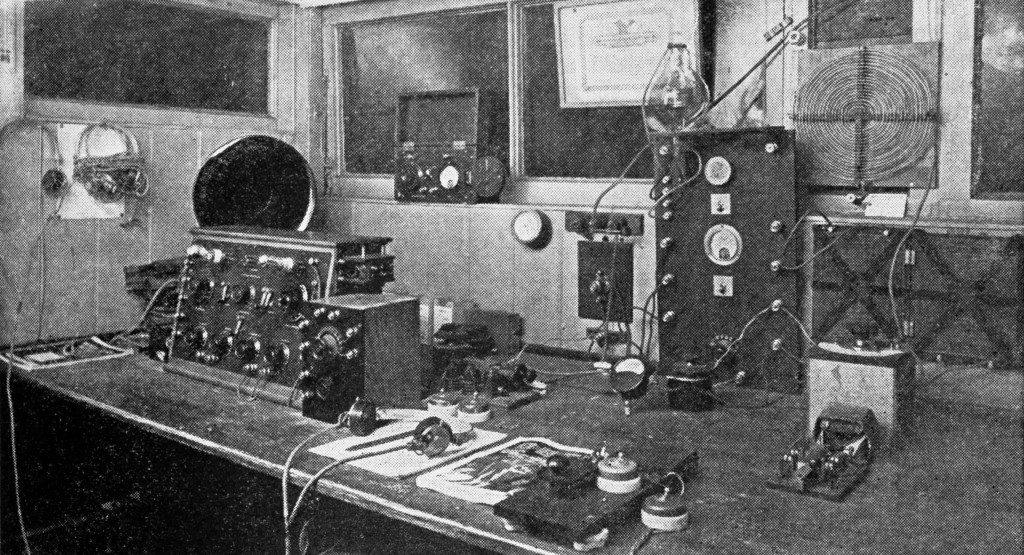

g2KF, ca. 1924

In December, a group operating PA9, the first amateur transmitter in the Netherlands, specially licensed for the fourth transatlantic tests of late 1923, was soliciting 100-meter tests with American amateurs. Those in Belgium and Italy awaited authorization and expected it soon as well. “It seems assured that this is but the forerunner of regular transatlantic operation,” predicted ARRL secretary Kenneth Warner accurately. “Oh! for the pen of a Wells, to picture the possibilities opened to amateur radio on both sides of the Atlantic, now that we are QSO!” he added, referring to science fiction writer H. G. Wells.

That the Deloy-Schnell QSO was no fluke was quickly becoming clear to everyone. Just a few weeks after the breathless reporting of that first transatlantic amateur contact, several others made it seem routine. Four British stations, another French station and one in the Netherlands all worked the US, with at least nine US stations making contact.2 And the Europeans were heard by many more amateurs in the US this time, as far west as the Pacific coast. Amateurs at last began to turn their attention away from 200 meters and down to shorter wavelengths. Warner observed that “Old-time amateurs who thought they had exhausted every thrill of the game are returning now, to tackle Europe.”

The first US-UK QSO was made by Warner himself, operating at Schnell’s station, 1MO (now referred to as u1MO using the new, unofficial intermediate ‘u’ as a prefix). He worked London amateur J. A. Partridge, g2KF, aided by Deloy at f8AB in the early morning hours of 8 December well past sunrise in London, which made it an astonishing feat. “A surprising feature of the communication was that as dawn wore on, on the other side, signals at 1MO became somewhat better,” he wrote. Several other UK-US QSOs followed on subsequent nights.

The second station in France to make contact across the ocean was f8BF, with u1MO on 16 December, again with the aid of Deloy at f8AB. The first QSO with Holland followed next with u2AGB working Dutch station PCII on 27 December, receiving a message for ARRL. u2AGB now held the record for most stations worked in Europe, with six QSOs in three countries. Deloy was copied as far as the Pacific Northwest. In fact, f8AB was the most often copied European station, often readable twenty-five feet from the loudspeaker.3

Now in regular contact, u1MO and f8AB lost track of the number of QSOs they’d completed and had passed more than 50 messages. All of the new QSOs were made in a range between 108 and 118 meters wavelength. “Probably we went thru so many years of vain struggling for contact with Europe simply waiting for a Deloy and a Schnell to try it on the shorter waves,” remarked Warner with unnecessary equivocation.

He did not quite understand why using shorter wavelengths mattered, pondering, “Radiation at the higher frequency is somewhat better, it is true, but not enough of itself to account for the difference; QRM is less, it is true, but that can’t account for it.” He chose at this point to agree with the theory that simply using an aerial cut to a length much longer than its fundamental wavelength resulted in this benefit. “If we built special small aerials for 100 meters we would be no better off than in past years on 200 meters,” he wrote. The steadiness of the short wave signals was also quite surprising, but apparently not yet convincing enough.

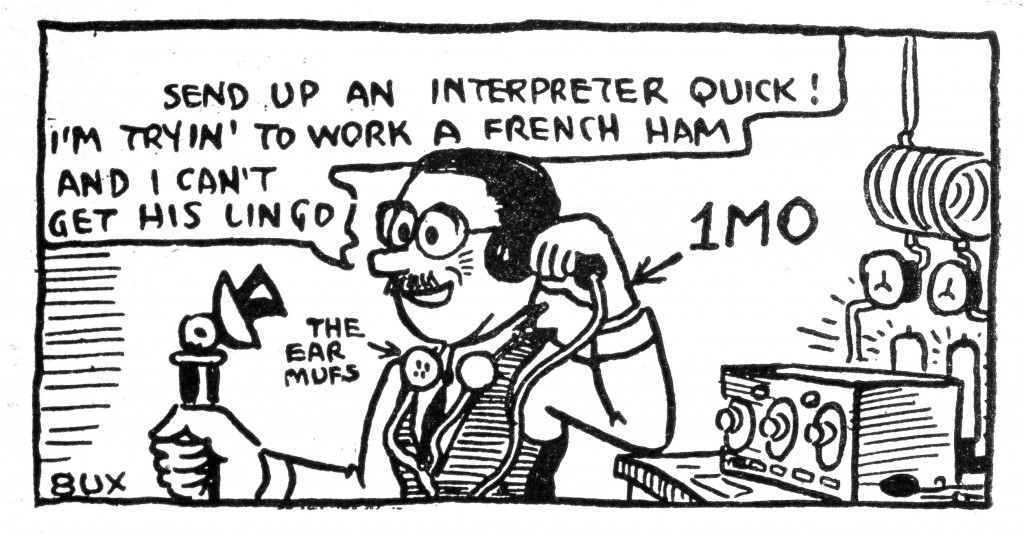

Cartoon of Fred Schnell, 1MO, from January 1924 QST

Expert opinions abounded in an effort to explain the successes at 100 meters. QST Technical Editor Robert S. Kruse took them on in rapid succession.4 First, it was not because of lower QRM. He pointed out that there was plenty of 100-meter QRM in the Hartford area from KDKA’s shortwave broadcasts, and from harmonics of very many lower frequency stations, including u6PL, who was completely inaudible in Connecticut on his primary wavelength! Other broadcast harmonics were troublesome too, including WOR in New York, which was a nuisance because of its “wavering nature,” as were the signals of various commercial spark stations.

He also attributed success to using aerials that were much longer than their natural wavelength, which usually involved tuning them with series capacitors. Kruse debunked ideas that such capacitors caused loss, saying they do not get hot so they could not be lossy, and yes, the resistance increases, but it’s radiation resistance—something good! That was lesson one. Lesson two was to get down below 200 meters. Even without an X (experimental) license, hams could operate at 150. The third was to make a wave meter so you can know where you’re operating. That was how Schnell and Deloy had done it, he asserted.

Among the messages Warner and Deloy handled was this one from Maxim sent to Marconi on 11 December 1923:

HARTFORD DEC 11

MARCONI LONDON,AMERICAN RADIO RELAY LEAGUE PRESENTS ITS RESPECTS AND THIS EVIDENCE OF DAWN OF INTERNATIONAL AMATEUR RADIO.

HIRAM PERCY MAXIM

Marconi’s reply came back via commercial wireless:

LONDON DEC 17

MAXIM

RELAY LEAGUE

HARTFORD CONN.PLEASE ACCEPT MY THANKS AND APPRECIATION WHICH I OFFER YOU AND ALL CONCERNED FOR YOUR CORDIAL MESSAGE TRANSMITTED AND RECEIVED BY AMATEUR STATIONS.

MARCONI.

Another pair was exchanged between Maxim and Eccles, g2GF, President of RSGB a few days later.

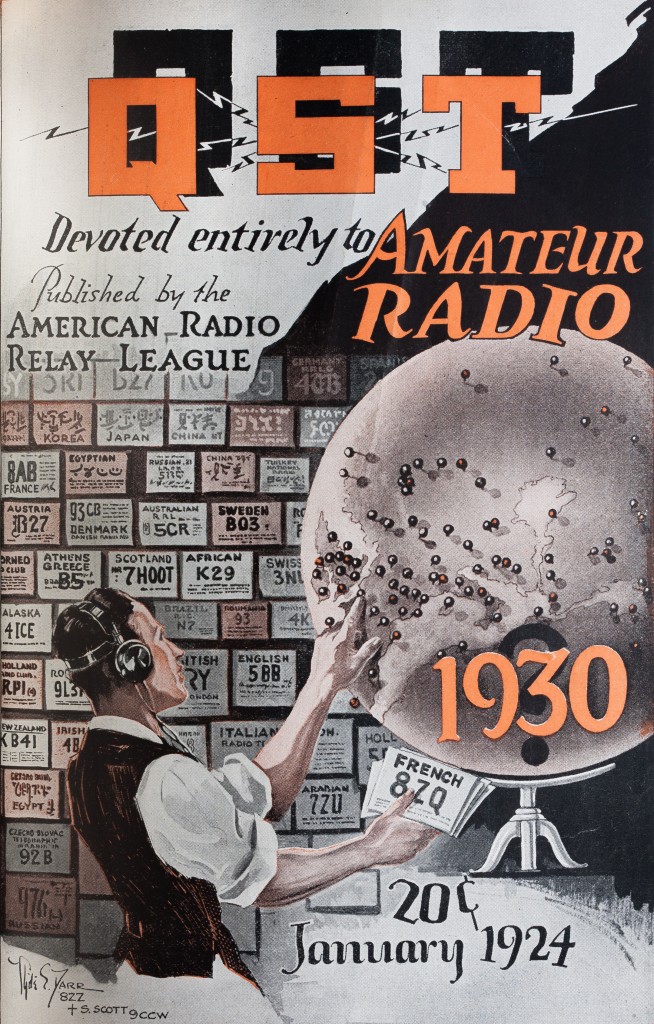

After a year’s worth of records and new international contacts, the January 1924 QST cover drawing by Clyde Darr, 8ZZ, depicted a vision of the near future: 1930 (no help needed from Mr. Wells). A US ham holding a fist full of QSL cards, and many more hanging on the wall from various countries, locates a new contact on a globe into which he’s sticking map pins. There are many already present on what appears to be the European continent.

After a year’s worth of records and new international contacts, the January 1924 QST cover drawing by Clyde Darr, 8ZZ, depicted a vision of the near future: 1930 (no help needed from Mr. Wells). A US ham holding a fist full of QSL cards, and many more hanging on the wall from various countries, locates a new contact on a globe into which he’s sticking map pins. There are many already present on what appears to be the European continent.

Although Darr saw his vision become reality much sooner than he had forecast, he became a silent key one month short of that new decade’s arrival after having drawn sixty-nine QST covers.5 (In the last month of his life he received hundreds of messages in a “message party” held in his honor.6)

As the weather turned cool, “Hot news is breaking every day, amateur records are being smashed to smithereens every time we turn around, and it’s a wild job to keep up with progress and get the stuff chronicled in the mag.,” wrote Warner. November alone brought several achievements: the first two-way transatlantic amateur contact, which also was the first 100-meter transatlantic contact by any radio service, the record on 100 meters; a new all time distance record when WNP worked u6CEU in Hawaii, who was using three 5-watt tubes in his transmitter; new relaying records in time and distance; the first contacts between Alaskan stations and the continental US; and two Australian stations were heard in California.

The fourth transatlantic tests had not yet officially reached their 11 January date for two-way contacts on 200 meters. As Warner noted, “the short waves have scooped the tests,” but he still expected many more on 200 meters once they began.

The tests ran as scheduled, despite being “scooped,” and the winners were announced in March 1924.7 The top prize went to R. B. Bourne, u1ANA, Chatham, Massachusetts, known previously for his early work with WNP, for the greatest number of station-miles, 390,460, having logged twelve British stations, nine French and one Dutch. In all, 20 British, 14 French, and 3 Dutch stations were copied. The UK’s W. W. Burnham now owed Kenneth Warner the clock they had wagered. (It’s unclear what happened to the green suspenders idea.)

About 1,200 interfering American stations were copied during the test and reported to the Traffic Manager, officially disqualifying them from winning prizes.

Comparatively unnoticed, the Transpacific tests ran in late October, during which 150 to 200 American and Canadian amateurs were received in Australia. Poor conditions prevailed with strong strays and harmonic interference. 6KA was the strongest station making it through from the US.8

Perhaps it was because the work with WNP was primarily focused on receiving messages from the MacMillan expedition as opposed to transmitting to them. Or maybe it was that no one yet fully understood the advantages of shorter wavelengths. It’s also possible that the pervasive belief that longer aerials were required made hams discount the relevance of the recent tests because they knew WNP had limited space. Whatever the reason was, no one told Don Mix about the recent accomplishments on shortwaves.

As spring of 1924 approached and the Bowdoin crew began to see some daylight around noon, signal strength had fallen off even more rapidly. The window of opportunity for hams in North America to work or even hear the expedition would now grow increasingly narrow as the expedition anticipated their return voyage. WNP was in two-way contact with home only sporadically through February and March, without having a single contact with 9BP, previously their most reliable link. Just enough communication got through to home in early April to convey that all was well with the expedition.9 The Bowdoin was now in constant daylight.

As conditions continued to worsen no further contacts were made and even the signals from the powerful commercial stations were difficult to copy at WNP. Facing terrible radio conditions and with the fuel supply dwindling, Mix recommended to MacMillan that he suspend the regular radio watch and from that point operated much less frequently until they began the return trip in August.

QST cartoon from January 1924

Frustratingly, the recent achievements on the short waves were still completely unknown to Mix. Though it now seemed like a logical suggestion, no one had gotten through to ask him to move to shorter wavelengths, specifically 100 meters, where it might have been easier to make contact even during the nearly twenty-four-hour daylight.10

As expected, the ice began to break up in June forcing them to abandon the longer aerials strung between the ship and the ice. The expedition left for home on 1 August. As they navigated south along the Greenland coast, conditions began to improve and on 26 August they made contact with u9CDV in East Grand Forks, Minnesota. Communication was mostly continuous from this point on, making contact with amateurs all along the way home, including Milton Mix, Don’s brother, operating from u1TS, Don’s home station.

On 20 September 1924 they arrived back at Wiscasset, Maine, having traveled more than 2,000 miles and spent 320 days frozen in the arctic winter ice.11 The crew was welcomed home by a gathering of several thousand people filling the small town on the village green.12 Maxim was one of the speakers in a ceremony at the Congregational Church.

Though never tuned to higher frequencies, WNP’s Zenith radio equipment had performed beyond expectations. Not a single tube or battery had needed replacement during the entire fifteen-month expedition.

After returning, Mix reported that while he had copied “scraps here and there” about the activity on shorter wavelengths, he “had no idea that they had been so successful.” He concluded that if he had been able to get down to 100 meters or so, the communications would have been much more reliable even during daylight.13

de W2PA

- “New World’s Relay Records,” QST, January 1924, 18. ↩

- Kenneth B. Warner, “The Progress of Transatlantic Communication,” QST, February 1924, 15. ↩

- Even when using vacuum tube audio amplification, hams continued the practice of expressing signal strength this way—a throwback to the days of crystal reception. See, for example, the chapter “Aerials, Attachments, and Audibility.” ↩

- S. Kruse, “What the Work With F8AB Teaches the A.R.R.L.,” QST, February 1924, 32. ↩

- Today Clyde Darr’s call sign, W8ZZ, is assigned to the Detroit Amateur Radio Association. ↩

- “Clyde Elden Darr, 1879-1929,” QST, February 1930, 25. ↩

- Kenneth B. Warner, “Transatlantic Tests Report,” QST, March 1924, 32. ↩

- Kenneth B. Warner, “Transpacific Test Report,” QST, February 1924, 40. ↩

- F. H. Schnell, “Bowdoin Continues but Communication Poor,” QST, May 1924, 30. ↩

- F. H. Schnell, “9ZT and 6CGS Work WNP,” QST, July 1924, 13. ↩

- F. H. Schnell, “WNP Nearing Home,” QST, October 1924, 19. ↩

- “The ‘Bowdoin’ Returns,” QST, November 1924, 16. ↩

- Donald H. Mix, “My Radio Experience in the Far North,” QST, November 1924, 17. ↩