As ARRL traffic manager Fred Schnell was beginning his voyage to the southern hemisphere with the US Navy,1 arctic explorer Donald MacMillan2 announced he would once again sail north with shortwave radio aboard the Bowdoin.3 The trip would begin in June 1925, and this time he planned to explore the north polar region using airplanes to determine whether any land existed there. The Bowdoin would be accompanied by a second ship, the Peary, captained by Commander Eugene F. MacDonald, Jr., president of Zenith, who would also be MacMillan’s second in command. The Peary carried three amphibian airplanes to be used to search for a postulated “vast Arctic continent” as they called it, near the pole. The National Geographic Society, representing the press, would collect news stories for further distribution.

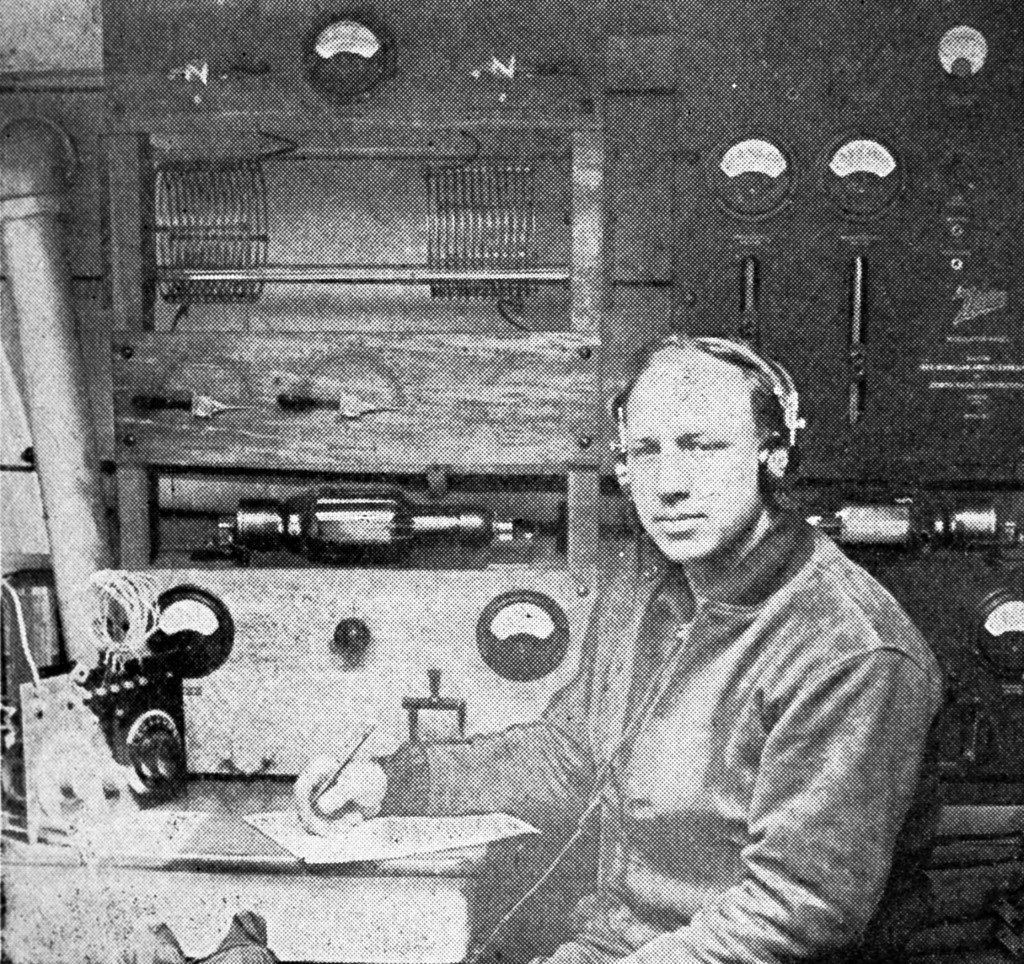

John Reinartz, 1QP, at the operating position of WNP aboard the Bowdoin

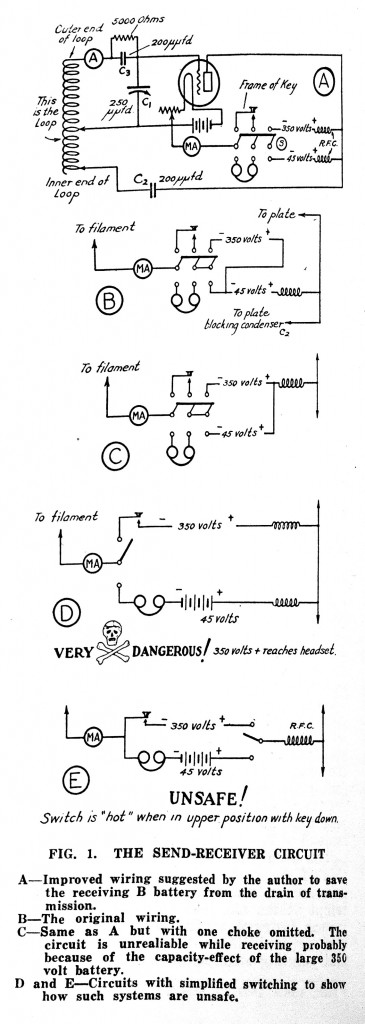

Macmillan asked amateurs around the world, and the ARRL in particular, to help maintain communications with the expedition. Following in Don Mix’s footsteps, John Reinartz, of 1QP-1XAM, who was also a Lieutenant in the US Navy Reserve Force, would serve as the expedition’s radio operator. Both ships carried radio equipment but only the Bowdoin would have shortwave capability to cover 20, 40, 80, and 160 meters. The airplanes were also equipped with transmitters for 40 meters capable of operating CW or phone powered by batteries in case of a forced landing.

This trip would be short, a dash up and back during the northern hemisphere summer months.4 Reinartz planned four three-hour periods of operation each day at 6:00 a.m., noon, and 6:00 p.m. Eastern Time. They would primarily operate on 40 meters wavelength with 20 being used more often as they got further north, expecting to rely on that band as the ship entered the region of constant daylight.

As on the previous expedition, the equipment, all donated, was designed and built by Zenith. It was planned out during a conference with Reinartz in March that included Professor Jansky of the University of Minnesota, and Don Wallace, 9ZT, along with Zenith designers Hassel and Forbes.

With easily interchangeable inductors, their transmitter could cover the 20, 40, 80 and 160-meter bands, producing 250 watts output power on CW and phone. It was powered by a 32-volt storage battery with backup, and dual 750-watt gasoline fueled generators. Cold, wet conditions at sea dictated using control panels made from dry maple boiled in paraffin which were supplied by the Thordarson Company, known for their transformers. Tested in Chicago at 9XN with antennas similar to the ones to be used aboard ship, its signal was heard loudly on 40 meters by Schnell at NRRL aboard the USS Seattle 1,600 miles west of San Francisco, and at 4AG in New Zealand—all during the daytime.

Three receivers were supplied: Zenith shortwave, Super Zenith broadcast, and a long wave receiver for press and time signals. The shortwave receiver consisted of a detector and two-stage audio amplifier and, like the transmitter, it had plug-in coils so it could cover the entire 15 through 220 meter range of wavelengths.

The Peary would carry a Navy 2-kilowatt, 500-cycle spark transmitter and a Zenith 2-kilowatt tube transmitter for communicating with its aircraft on 500 meters. The aircraft were outfitted with battery operated, low power, single tube shortwave transmitters operating between 37 and 42 meters, using a modulator tube for phone operation. They also had standard Navy transmitters operating at 500 meters. Two portable receivers with loop antennas would be used by exploration parties to find their direction back to the planes and ships. The aircraft antennas consisted of a trailing wire while airborne and a mast-supported single wire when on the ground.

The Bowdoin and Peary sailed together from Wiscasset, Maine on 20 June as planned, bound for Greenland, with Reinartz at the key of WNP. The Peary’s station, WAP, was operated by Paul J. McGee, prewar 9AE, and another member of the Zenith technical staff.5

Shortwave operation made all the difference—the expedition was in nearly constant communication this time. From their northern locations, communications were reliable even in daylight on the 20-meter band, exceeding their expectations. The Bowdoin arrived at Etah, Greenland, its permanent base, on 2 August. Its first contact, made that same day, was with 9CXX, on 16 meters.6

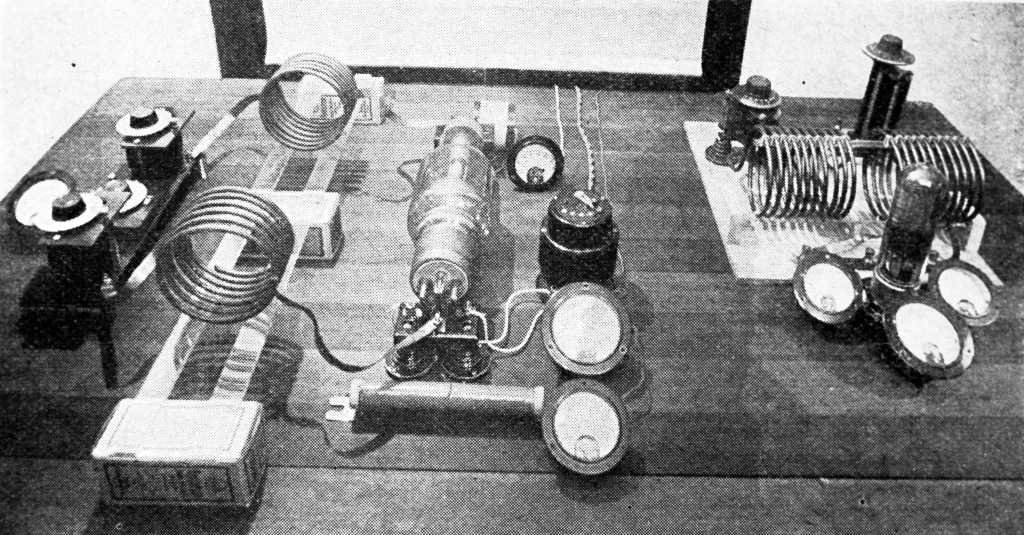

Fifteen-year-old farm boy Arthur A. Collins, who “believes in simplicity for efficiency,” had been involved in radio since he was nine. The owner and operator of 9CXX in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, he became one of the main channels for communicating with the expedition.7 His transmitter was a 1-kilowatt input, single tube in a modified Reinarz design. A smaller transmitter used a 203A tube in a circuit laid out breadboard-style to enable him to rapidly change it around.

Teenager 9CXX’s transmitter – one of the first Collins-built rigs.

Despite being on a farm, his biggest problem seemed to be the lack of a friendly environment for antennas. A QST profile noted “9CXX has never been blessed with a good antenna location. Due to opposition it has been impossible to erect a good antenna.” So, he used a 50-foot long wire with 48-foot counterpoise 20 feet below it.

9CXX later became W0CXX and established the Collins Radio Company.

Failing to find any evidence of an arctic continent, the Bowdoin returned to Wiscasset on 10 October 1925, and was greeted by ARRL secretary Warner and others. Many messages were handled during their stay in the arctic. This included the WNP logs from July through October, received in full by 9CXX, and printed in QST.8 The winner of the silver cup for most messages handled went to Donald C. S. Comstock, 1MY, with 9CXX and 1ARE as runners up.9

The successes of the Macmillan expeditions inspired other explorers to use shortwave radio. By 1927, the ARRL Communications Department was participating in, and regularly reporting the status of, seven expeditions in progress at once.10

![]()

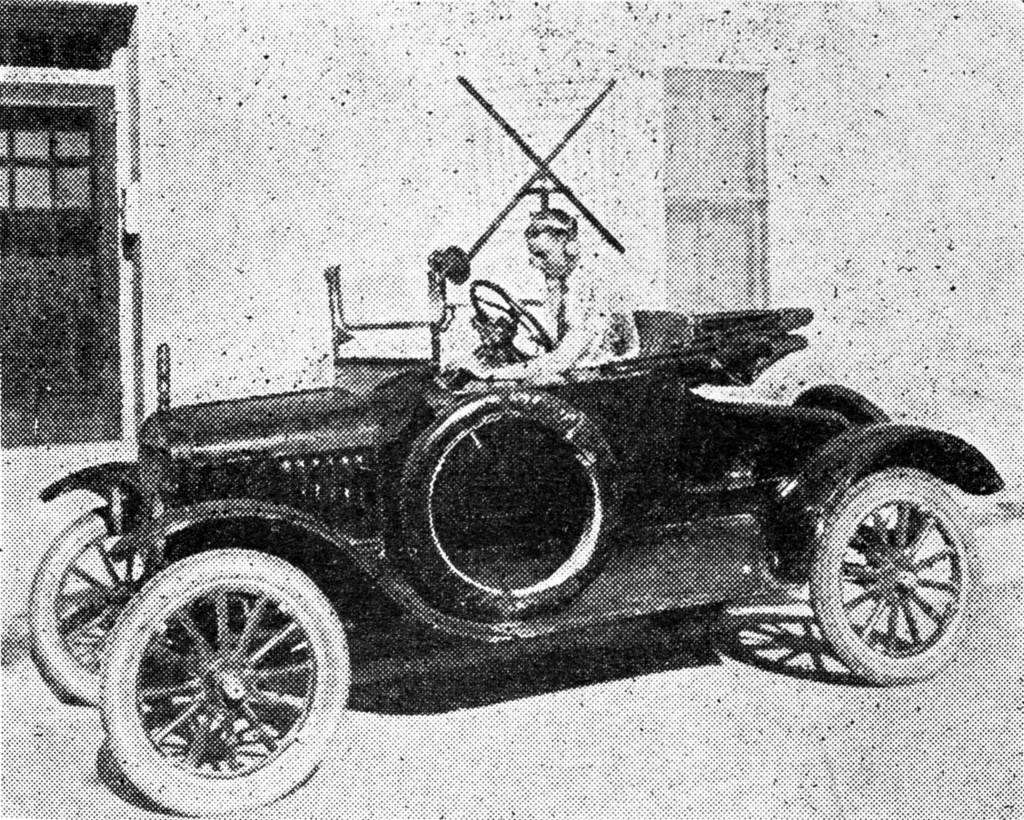

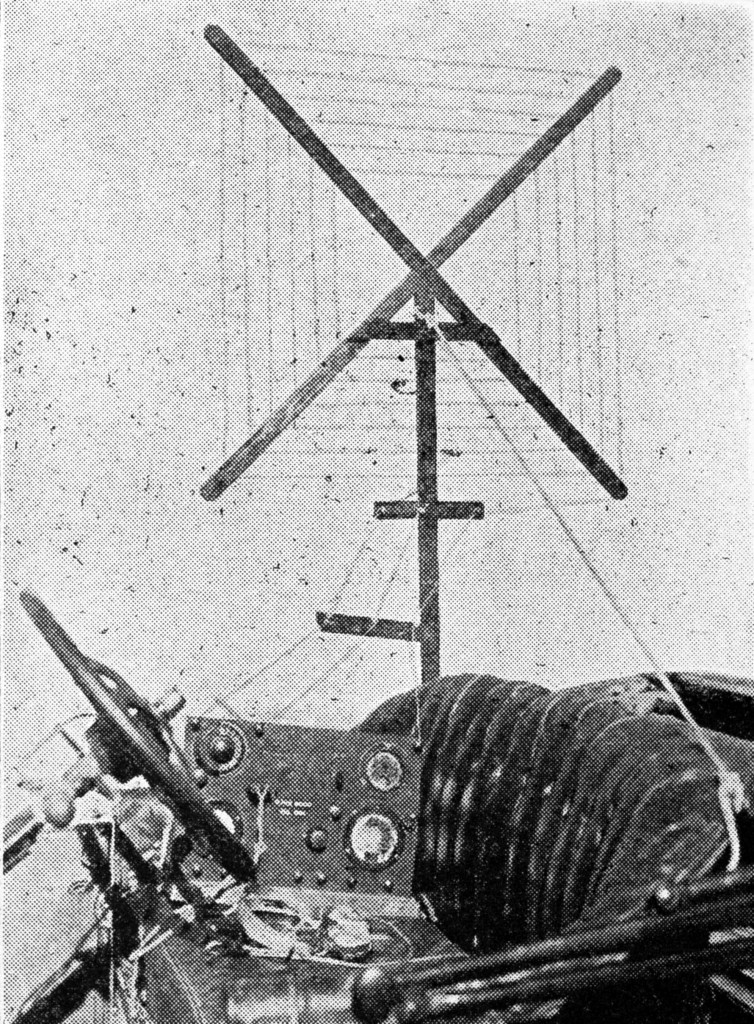

Wright at the wheel of 6GD/mobile

Lesser in time, distance, and seriousness, another trip north was run that same summer by a handful of college students in Arizona.11 Oliver Wright, 6GD of Tuscon, had fixed up his Ford roadster into what he called a “true radio flivver.” He accomplished this, he said, “in cahoots with the University of Arizona radio station 6YB,” himself being “an inmate of the institution in question.”

Some appropriate decoration was called for so he added his call sign and 73 to the rear-mounted spare tire cover, affixed a burned out vacuum tube to the radiator cap, and connected a key to the car’s horn which, he claimed, sounded something like “an ancient rotary gap.”

Some appropriate decoration was called for so he added his call sign and 73 to the rear-mounted spare tire cover, affixed a burned out vacuum tube to the radiator cap, and connected a key to the car’s horn which, he claimed, sounded something like “an ancient rotary gap.”

For actual radio operation Wright and the club constructed an 80-meter transmitter which could also be used as a regenerative receiver with proper switching, and a 30-inch square loop antenna with six turns of wire, mounted parallel to the side of the car to minimize wind resistance. Four turns of the loop were hooked into the plate circuit and two in the grid, according to the Hartley circuit design.

He mounted the transmitter-receiver to the right side of the seat (this car had only a single bench), leaving “plenty of room left over for two operators without crowding.”

A switching arrangement kept high voltages away from the driver. The key, for example, series-connected in the plate circuit, had to be hooked up with its frame on the filament side of the transmitter. Reversing this would mean “you would most certainly get a very nasty jolt as you are practically certain to be touching the metal body of the car at some place and thereby completing the high voltage circuit through yourself,” wrote Wright.

Initial tests managed to establish one-way contacts only—ignition noise in the receiver drowned everything out and required shielding.

Their mission was to operate from the car while driving thirty-two miles northeast to Oracle, and attempt to maintain contact with 6YB back on campus. They considered this a challenge since the university’s broadcast station could not be heard in Oracle because an intervening mountain range blocked its signal. As they set out one hot, sunny morning, they were easily able to stay in contact with the club until the paved road ended six miles outside the city making it too difficult to operate while moving. It was hard enough keeping a transmitter on one wavelength when anchored to solid ground. Nevertheless, stopping along the way they were able to consistently QSO 6YB all the way to their destination.

Taking the time to both advertise and forestall questions, Wright reported that “before starting the trip we pasted on the windshield a little sign giving our calls, the purpose of the test, the wavelengths used and a brief description of the set, winding up with a fervent request that no fool questions be asked because we were busy. It worked beautifully except for one old gentleman who stopped and asked: ‘Well, how’s the music, boys?’”

![]()

de W2PA

- See, Army Vacation or Navy Cruise ↩

- See, High Latitudes and Low Wavelengths ↩

- R. H. G. Mathews, “The Navy MacMillan Expedition,” QST, June 1925, 33. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “Short-Wave Communication with WNP,” QST, July 1925, 20. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “MacMillan Shoves Off,” QST, August 1925, 15. ↩

- F. E. Handy, “WNP,” The Traffic Department, QST, September 1925, II (second page of the appendix) – no link in the QST archives available for the appendix. ↩

- “9CXX,” Amateur Radio Stations, QST, October 1925, 53. ↩

- F. E. Handy, “WNP,” The Traffic Department, QST, November 1925, III (third page of the appendix) – no link in the QST archives is available for the appendix. ↩

- F. E. Handy, “WNP,” The Traffic Department, QST, October 1925, II (second page of the appendix) – no link in the QST archives is available for the appendix. ↩

- See, e.g., Communications Department, QST, March 1927, no link in archives available for appendix. ↩

- O. Wright, “Loops and Fords,” QST, July 1925, 33. ↩