The fourth National Radio Conference convened on 9 November 1925, with seven hundred delegates from all sectors of the radio community present. Although attendance was larger than at any previous conference, it concluded its work in only three days, the shortest of any.1 As before, Maxim, Stewart, and Warner represented ARRL and the US amateurs.

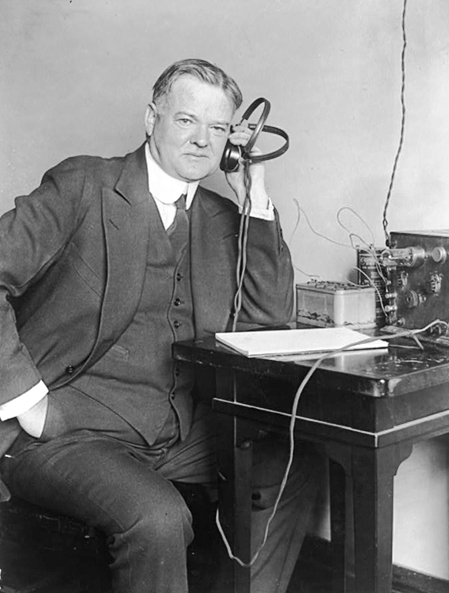

Department of Commerce Secretary, Herbert Hoover

Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover once again presided over the conference and set the tone. In his opening remarks he said that amateur radio “has found a part in the fine development of the American boy, and I do not believe anyone will wish to minimize his part in American life.” The boy and his radio had come a long way since the days of squeak boxes.

The conference was divided up into nine committees: Allocation, Advertising, Licenses, Regulations, Marine, Amateur, Interference, Legislation, and Copyrights. Committee 1, frequency allocations, and Committee 6, amateur radio, were the two most relevant to the hams.

Maxim chaired Committee 6; R. Y. Cadmus, Supervisor of Radio for the Third Radio District, acted as secretary; and its other members were all prominent hams. “This was 100% an amateur committee and its meetings were ham rag-chews,” reported Warner. The committee’s primary recommendations were that the Department of Commerce should cease licensing spark transmitters altogether; allow amateur phone transmitters to use 3,500 to 3,600 kHz, observing silent periods; and publish a list of amateur stations annually. Last but not least, And most importantly it urged Commerce to appeal to Congress for increased funding “for the proper control and encouragement of radio.”

Commercial broadcasters’ attitudes toward the Department and regulation had changed markedly since the preceding conference. While they previously favored a hands-off approach by the government, they now recognized that congestion had reached the point where tight regulation was the only remedy and voted to grant regulatory authority to the department, and to Hoover in particular. They recommended that the number of stations be reduced through “discontinuance” (presumably meaning non-renewal of license or otherwise ending a station’s permission to operate after cessation), that new stations be granted licenses based primarily on public interest, and that the Congress enact legislation to put the Secretary of Commerce in charge of administering radio—a significant increase in authority over what was specified in the 1912 law.

Radio manufacturer A. H. Grebe, a prominent advertiser in QST, led a push to extend the broadcast band down to 150 meters. The engineering community and the US Navy joined amateurs in opposition. More importantly, the broadcasters themselves were split on the issue, with the smaller but more numerous Class-B station owners joining the opposition, reasoning that such a move would mostly benefit the big Class-A stations at their expense by driving them all down to the shorter wavelengths, giving the Class-A all the choice, longer wavelengths.

But the conference decided that reallocation would accomplish little reduction of interference at the cost of “certain damage” to the amateurs. Moreover, it would make existing receivers at least partly obsolete. The rejection came as no surprise given Secretary Hoover’s opening remarks that stated much the same things before the proceedings had even begun.

Another proposal would give 171–200 meters to commercial use in Hawaii. The Mutual Telephone Company there claimed that it would allow inter-island communication that was not possible on 133–150 meters according to their experiments. Maxim and Committee 6 members were not convinced and recommended against adoption in Committee 1, which agreed.

The allocations committee also moved to ban spark below 200 meters, which would effectively ban it from all amateur operations. This too was agreed on and recommended by the full conference.

The Navy presented its proposal for enhancing naval communications, something largely ignored by the 1924 conference, which had been preoccupied with broadcasting. The proposal was adopted after some minor modifications. The committee moved to permit the sharing of the 80 meter band by the Navy for aeronautical operations. The Navy’s plan also proposed holding wavelengths shorter than 16.6 meters as “experimental reserve,” though the amateur bands at 5 meters and 75 cm would be retained.

When it adjourned, the full conference had recommended that all existing amateur allocations remain intact, including the 150 meter band.

In a letter to Maxim, Secretary Hoover thanked him for participating and expressed his satisfaction that amateur radio had fared so well there, or at least had not been harmed,2 writing,

It is always a pleasure to see you at the radio conferences and I was very glad that you were able to attend the one which has just adjourned. As you know, I have been especially interested in the amateur side of radio. There was no desire manifested in the conference for any interference with amateur operations. It is gratifying to know that the conference did nothing to interfere with the amateurs in the slightest degree. I thank you very much for your service as chairman of the amateur committee.

![]()

Later that winter, the ARRL board met in Hartford for the first time since adopting the new constitution two years earlier. On the heels of a successful regulatory conference and strong endorsement by the Secretary of Commerce, it was time for a well deserved, self-imposed pat on the back for the League, and acknowledgement of its prime mover. Maxim was unanimously reelected as president, as was Charles Stewart, 3ZS, as vice president.3

Citing the “deep admiration and affection” with which Maxim was held by the members, the board resolved “that in re-electing for two more years of leadership the beloved founder and inspiration of our League, we offer to him this unanimous expression of our appreciation for his efforts, our confidence in his ability and leadership, and of our deep affection.”

The board renamed the Traffic Department to the Communications Department and changed its manager’s title to match. They changed the department’s structure too, dividing it into a larger number of regions called sections, each run by a Section Communication Manager elected by the members for a two-year term. The sections were defined by the ARRL Communications Manager in collaboration with the Canadian General Manager, for “the Dominion of Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador,” and by the Communications Manager and ARRL directors in “the United States, its island possessions or territories, or the Republic of Cuba.”

![]()

The US Senate Committee on Interstate Commerce held hearings on two bills and would await action by the House, where a new bill by Congressman White (HR 9108), based on the November radio conference, was being considered.4 Supported by all radio interests, not just amateurs, it was judged likely to pass with minor modifications, if any. This bill included the establishment of a nine-person National Radio Commission, appointed by the president, to which the secretary could refer matters of rule making. Once referred, the commission’s rulings would be binding on the Secretary. Decisions of either the commission or the Secretary could still be challenged in the Court of Appeals of the District of Columbia.

When the White bill was passed by the House on 15 March,5 the only change from its previous version was the commission consisting of five commissioners, one from each radio zone, instead of nine, one from each inspection district. But the Senate committee on Interstate Commerce, which also had a say in the matter, had not reported any of the bills it was considering. Everyone would have to wait.

Just as the new radio bills stalled for the moment, a legal decision sent shockwaves through the radio community,6 threatening its entire regulatory foundation. A court sided with Zenith in challenging the authority of the Secretary of Commerce by asserting that since the company was engaged in experimental work it could legally choose any wavelength outside of the 600 to 1,600 meter allocation and operate there under the letter of the 1912 law. The US Attorney General took this a step further and asserted that the government had no authority over radio beyond the 1912 law, in which neither broadcasting nor shortwaves was mentioned at all.7

The court’s decision did not merely affect one company (incidentally, one founded by an amateur). It further meant that none of the band allocations at wavelengths shorter than 200 meters was enforceable under the law, threatening a return to on-air chaos. In reality, this should have not been very surprising. Most everyone involved had known or suspected just this sort of weakness in the law for some time, but in the interests of harmony on the air all parties in all radio services adhered to the new regulations that emerged from Hoover’s radio conferences—until now. A court ruling was hard to ignore. Nevertheless, the League stood behind the agreements made at the Fourth National Radio Conference, “law or no law.”

Although the acute and newly urgent need for legislation was obvious, it now looked less likely to pass before the Congress would adjourn and flee Washington in early June. The primary point of disagreement was over who would get authority: a new commission, the Secretary of Commerce, or a combination.

While the White bill passed in the House, and another called the Dill bill passed in the Senate, no reconciliation was completed in time for adjournment.8 And although Congress managed to pass an emergency resolution giving the Commerce department authority to regulate, even that did not make it to signature before its members left town.

So the country was left without new radio legislation, no legal authority for the Commerce Department, and everyone stuck with the “ancient” 1912 law. Hoover’s further appeal to the Attorney General for an opinion went nowhere. Nothing could happen until the congressional conference committeemeeting in November preparing for the new Congress a month later. For now, everyone on the air was left up in the air.

Secretary Warner reiterated the League’s voted policy that amateurs should adhere to the agreements of the Conference, unlike some broadcasters that were already making changes previously considered illegal, such as changing their wavelength, power, and hours of operation on their own accord. Unlike amateur radio, they had no cooperative agreement among them or national organization to impose guidelines of behavior.

The Department of Commerce reported there were 14,902 active amateur radio stations in the US as of 30 June 1926. Their behavior would weigh heavily once legislative action resumed. “You fellows haven’t any idea how much strength your representatives at Washington will gain if they are able to say in the future that amateurs did not take advantage of the technical breakdown of authority to run amok and become radio pirates, but that instead they were square-shooters and played the game like sportsmen!” advised Warner, mixing at least three metaphors.

Frustration continued into fall when, even with general agreement among radio services to endorse the White bill, the new Congress again could not seem to get reconciliation done.9 Not surprisingly, Warner suspected it was due to politics, specifically members of congress who did not want Hoover to get credit for bringing it all together.

This time, however, an emergency joint resolution was signed into law requiring applicants for new licenses or renewals to file a waiver giving up any claim to specific wavelengths. This was apparently a stopgap measure designed to prevent broadcasters from asserting vested rights to operate by putting up a new station and thereby staking a claim to whatever wavelength they chose—a kind of spectrum squatting.

Finally, in mid-winter there was progress. A successful reconciliation of the White and Dill bills on 26 January 1927 was followed quickly by passage in the House only three days later. The Senate debated the combined measure into mid-February.10

The new bill retained the basic intent of earlier ones: to not prescribe specific regulations but rather to vest the power to regulate in an administrative authority. Still unresolved was the matter of what that authority should be, a new commission or the Commerce Department. In a compromise they decided that a commission would be in charge during the first year, the critical time during which most of the regulatory structure would be defined. Then, the secretary would take over with the Commission acting as a path for appealing decisions he made, and retaining the power to revoke licenses. In the case of a refusal to grant a new license, a further appeal could be made to the DC Court of Appeals, and a revocation could also be appealed in a local US district court. This seemed to satisfy everyone who worried about concentrating authority in any one place.

During its formative first year the commission would classify all stations and specify their wavelengths, and the secretary and Commerce Department would issue operators’ licenses, assign call signs and perform inspections. Much then was riding on the choice of commissioners, since they would shape radio regulation for the foreseeable future.

With the exception of government, amateur, and mobile stations, anyone building a new station would be required to obtain a construction permit first. Similarly, a provision protecting the secrecy of transmitted messages also exempted amateurs and broadcasters. Together, these two statements—both of which explicitly mentioned amateurs—put to rest the earlier fears of amateurs being excluded.

As fate or chance would have it, the final version of the radio bill was passed just after deadline for March 1927 QST, forcing a last minute rewrite of the following month’s editorial. Those amateurs who did not hear the news on the air found out in April QST that the bill was signed into law by the president on 23 February 1927.11

To form the initial radio commission, the president appointed Rear Admiral William H. Bullard, USN (retired) as its first chairman, along with O. H. Caldwell, editor of Radio Retailing, Judge Eugene O. Sykes, former justice of the Mississippi Supreme Court, Henry A. Bellows, Director of station WCCO in Minneapolis, and J. F. Dillon, Supervisor of Radio for San Francisco, respectively representing the five radio zones as commissioners. They would each serve terms of various lengths ranging from two to six years, but their successors would thereafter serve uniform, six-year terms. The staggering of initial terms was designed to insure a continual, overlapping turnover of seats.

As long and arduous a task as it had been, passing the compromise law was the comparatively easy part. The commissioners would now face the daunting task of dealing with claimed rights of various sorts having to do with continued use of facilities, wavelengths and existing licenses, while simultaneously processing new licenses for every station, as required by the law. Everyone in radio expected them to spend the majority of their time on matters affecting broadcasting, the service most in need of restructuring.

“This country is now about to test in practice a theory which has been largely expounded in recent years: that a radio law should contain no technical stipulations, no guaranties to anyone, but should give discretionary power in regulations to an administrative authority, We shall very soon see,” commented Warner. QST printed the complete text of the new, 41-section radio law, occupying six pages.12

As a “wild scramble for radio privileges” followed the passage of the new statute, all parties continued to endorse amateur radio. In fact, they sought the opinion of the ARRL even on matters outside the amateur radio realm.13 Maxim attributed this to a record of good policy making by the League’s Board of Directors and “being on the right side of big questions as far back as anyone can remember.” He warned, however, that all the good will that had taken so many years to build could be wrecked in only days if amateurs failed to carefully follow the new regulations.

With the force of law now backing the band allocations, carefully respecting their boundaries was more important than ever. Yet there continued to be far too much out-of-band or off-wave operating going on, especially in the crowded 40 meter band.14 Even though accurately measuring frequency was still difficult, there was no excuse for it on 40 since the band limits were easy to find, marked by two readily received high power stations on its edges: NAA at the bottom and WIZ at the top.

Facing rumors that the League was endorsing the surrender of the 150 meter band to broadcasting, the ARRL stated flatly that it remained committed to defending all amateur allocations. There was, however, a feeling among amateurs that phone operation, which now primarily occupied that band, should be concentrated there and that the new telephony allocation at 80 meters had been a mistake. The phone allocation at 150 should be increased, many argued. And, by the way, ICW should be eliminated just as spark had been.

![]()

President Coolidge named the Federal Radio Commission on 1 March 1927 and it began work immediately.15 Admiral Bullard, being out of the country, authorized its start up and the commission voted Judge Sykes to be the Vice Chairman. Although the congress had adjourned without appropriating funds for the commission’s operation, it was able to get going by borrowing people and equipment from other agencies.

The Department of Commerce established a new Radio Division on 8 March, moving the function out from under the Bureau of Navigation where it had organizationally sat since 1912. The Bureau’s offices moved out of the Commerce building and its space was turned over to the new Radio Division and the FRC.

One week later the Commission met for its initial session. Its first official act was to indefinitely extend all amateur and ship licenses, and authorize the Commerce Department to issue temporary amateur station licenses to new applicants pending the establishment of new regulations. In parallel, the Commerce Department extended all operator licenses valid at the time of the law’s passage to their originally designated expiration date. The two license grades would be: Radio Operator, Amateur Class, and Temporary Amateur License, eliminating the Amateur Extra First Grade, only six of which had been issued since its inception four years earlier.

Operator license examinations would consist of a sending and receiving test in Continental Morse at a speed of ten words per minute, and a written test covering regulations and operation of radio apparatus. The Temporary Amateur License would be granted when a test could not be given, pending an opportunity to give one, and be valid for at most one year.

The Commission held hearings on broadcasting matters between 29 March and 1 April. Accompanied by Stewart, Warner attended and delivered a statement prepared by the ARRL board. Opening with a brief history of amateurs’ technical contributions and operating achievements, he appealed for rejection of broadcast band expansion into the 150 meter amateur band, specifically citing experiments in amateur radiotelephony.

The commissioners were unanimous in opposing any further expansion of the broadcasting allocations with specific support for preserving the amateur 150-200 meter band coming from Commissioner Bellows. Although the band was not taken away from amateur use, the Commission would allow experimentation by individual broadcasters who could show that such experiments would serve the public interest.16 The Commission’s original wording left open the possibility that the band might be made available to broadcasters in the future for both radio and television. For now, however, the regular broadcast band remained confined to 550 to 1500 kHz.

After fifteen years, numerous challenges to their existence, and a near breakdown of radio regulation altogether, amateurs were finally protected under the Radio Act of 1927, at least in the United States. The law established a basic framework for radio regulation whose influence continues today.

More familiar than most with international radio, however, hams knew they could not relax. Threats on the world stage lay ahead.

![]()

de W2PA

- K. B. Warner, “The Fourth National Radio Conference,” QST, January 1926, 33. ↩

- Communications, QST, February 1926, 58. ↩

- “The Board Meets,” QST, April 1926, 27. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “Radio Legislation Pending,” QST, March 1926, 44. ↩

- Strays, QST, May 1926, 20. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “The Problem of Regulation,” QST, June 1926, 7. ↩

- C. B DeSoto, “Two Hundred Meters and Down,” The American Radio Relay League, Inc., 1936, 132. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “Loyalty,” Editorial, QST, September 1926, 7. ↩

- K. B. Warner, Editorial, QST, February 1927, 7. ↩

- K. B. Warner, Editorial, QST, March 1927, 7. ↩

- K. B. Warner, Editorial, QST, April 1927, 7. ↩

- “The New Radio Law,” QST, April 1927, 39. ↩

- H. P. Maxim, “ARRL Policies,” QST, May 1927, 8. ↩

- K. B. Warner, Editorial, QST, May 1927, 7. ↩

- Kenneth Warner, “Radio Regulation Returns,” QST, May 1927, 15. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “150-200 Meters,” QST, June 1927, 31. ↩