ARRL membership was free in 1915; QST would be a new and separate entity. With a mixture of enthusiastic optimism and a strong belief in the necessity to organize hams across the country, Maxim and Tuska were confident enough of the magazine’s future to risk some of their own money (mostly Maxim’s, one would think) to get it rolling. The state of the world and the country at this point made such optimism a little difficult to muster. In fact, their first issue’s lead article noted the “serious national questions” pertaining to defense and predicted that radio would likely play an important, though not yet fully understood, role. They were right.

Signing as “Chairman,” Maxim had written a letter that August to US Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels in which he described the ARRL and the amateurs’ accomplishments in relaying messages and aiding in emergencies. Maxim offered their services to the government, believing they would be valuable assets, especially since most of the members’ stations were situated along both coasts.1 Writing with evident pride, he explained that although the League consisted of “middle-aged men, young men, and boys” there were many amateur stations that were more capable than commercial ones. He also enclosed a current List of Stations.

In reply, Daniels welcomed his “patriotic offer.” He directed Maxim to correspond directly with the Superintendent of the Naval Radio Service, who was in charge of radio operations including how to use non-Navy facilities if necessary, and would be interested in as much detail as Maxim could supply. In particular, foreshadowing regulatory disputes yet to come, he expressed interest in “the method employed for the interior control of the amateur stations constituting the League.” Daniels (whose assistant secretary at the time was Franklin Delano Roosevelt) believed that the Navy needed new technology, so he had created the Naval Consulting Board, appointing Thomas Edison as its chairman.

Maxim had also written to the Secretary of War with a similar offer. A different kind of reply came back from Lt. Col. Samuel Reber, Acting Chief Signal Officer of the Signal Corps, formally known as the U.S. Army, Aviation Section, U.S. Signal Corps. Reber thanked him for the letter and using very formal language said, in effect, we’ll call you when and if we need you.

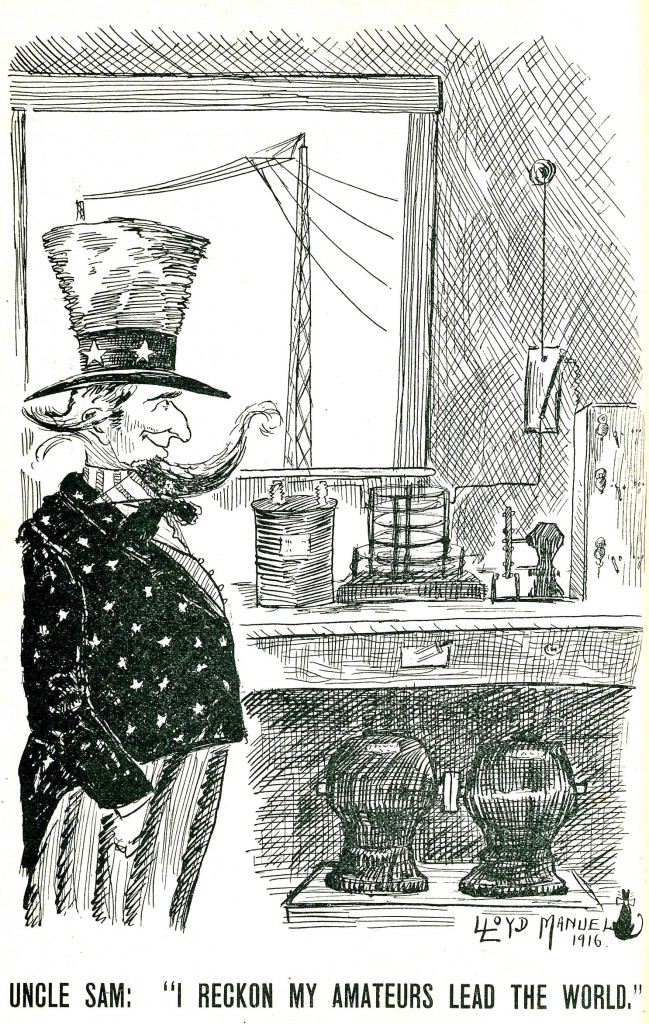

From the beginning, hams had a sense that with their operations and organization they could and should contribute to the public good. Maxim summarized that “the organization of our League, in efficient working form is a work which is of national importance, and we may have the knowledge that it represents a patriotic and a dignified effort.”

Judging by the letters that appeared in the second issue in January, the first issue had been received enthusiastically by the League’s members.2 Jacob Weiss wrote the first letter to QST, calling its premiere issue “a peach,” and reported some on-air activity. Robert Campbell, Jr., also wrote in to say that QST is “all to the mustard,” which I suppose meant “good” since Mr. Campbell ordered a subscription and League “license.” Other letters talked of stations “working” each other, so that particular term was already in use.

de W2PA