For nearly a year, hams had been operating in their first assigned band of wavelengths, 150 to 200 meters. They had also been experimenting below 150 meters by special government permission, dramatically demonstrating the effectiveness of the shortwaves with the first transatlantic two-way contacts, and marking the birth of international amateur radio. But why, they wondered, had the government designated the spectrum below 150 meters as “reserved?” Clearly that was a temporary state of affairs. What would come next for the shortwaves, which hams had proved were not as useless as the radio establishment had thought?

The spring of 1924 brought a new radio bill to the House of Representatives Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries, the legislative body still responsible for radio regulation and policy. Congressman Wallace H. White of Maine was again at the helm as sponsor and committee chairman.1 2 This time it was not simply another modification of the aging and obsolete 1912 law but an entirely new one designed to replace it. Still, the new bill was similar to the previous one carrying White’s name, in that it would eliminate technical details from the law itself and give the secretary of commerce authority over every aspect of radio law, including defining the classes of operation. Recognizing the rapid recent changes occurring in the radio art, the bill was intended to create a legal “administrative skeleton” that could survive unanticipated technologies yet to come, something the 1912 law could never have done—its major flaw. While amateurs had received firm support from the secretary in the past, nothing in the current law would prevent future appointees from changing all that. Of greatest concern to amateurs: there was no explicit mention of the amateur service in the bill, or of any other radio service for that matter. At the same time, given the accelerating advancement of technology, expecting a new law to contain all the technical details pertaining to every service was impractical, if not impossible. It would be much too complex and would quickly become outdated. Therefore the League was taking a qualified, if resigned, stance on the proposed law.

Hams would have to take their chances to a degree, but some crucial modifications would have to be made before the League could endorse it. Of greatest concern was the “discretionary power” the proposed law would grant to the secretary of commerce. Regulatory decisions made under such a law could not be reviewed or challenged in the courts, and therefore would make the secretary the “absolute dictator and czar of radio,” as ARRL secretary Kenneth Warner described it.

Amateurs were not alone in calling for a change during the congressional committee’s hearings—the other radio interests shared the same concern. One suggested remedy was simply to remove the language that referred to the secretary’s discretion—expressions such as “as he may deem necessary.” Another suggestion, foreshadowing what eventually happened, was to place the authority in the hands of a “Radio Commission” rather than a single person. RCA and AT&T favored the bill as it was, but Westinghouse, along with most independent broadcasters, opposed it.

One month later, an amended Senate bill emerged to be considered by Congress in its fall session. The new wording limited the discretionary powers of the secretary, provided for challenges to rulings, and—most importantly—explicitly named amateur radio in several places. The League’s concerns had been largely satisfied.

Elsewhere in the Senate, the Committee on Finance, perhaps wanting to be involved in the radio boom too, was considering a ten-percent tax on all radio equipment and parts, that would affect all services including amateur radio.3 But it was proposed based on the misconception that a single manufacturer, RCA, was setting prices as a monopoly. After receiving protests from around the country and being schooled on the characteristics of the market, the proposal was thrown out.

![]()

The call for access to the shorter waves was soon answered. On 25 July 1924, the Bureau of Navigation, Department of Commerce, announced that amateurs would be granted access to five new bands of wavelengths at 75 to 80, 40 to 48, 20 to 22, and 4 to 5 meters4, added to the already existing band at 150 to 200 meters. In trade, all access to wavelengths above 200 meters was sacrificed to help enable broadcast expansion.5

Although the League had hoped for access to the band from 105 to 110 meters (where the landmark recent transatlantic QSOs had taken place), only special license holders could apply to use it for now, and only for experiments with various classes of government and commercial stations, particularly the Naval Research Laboratory and the arctic expeditions. General access to the band would be revisited at the National Radio Conference to be held in Washington in September.

Besides notifying the press, Commissioner D. B. Carson sent a letter to the ARRL for distribution. Carson relied on QST to get the word out, stating that it was not possible to notify each individual amateur because of “the work involved.” Printed copies of the six paragraphs of new regulations were sent directly only to the government’s radio supervisors.

CW alone would be allowed on the new bands—no spark or phone. This included all forms of what was referred to as tube telegraphy, including vacuum tube circuits with battery, generator, partly rectified, unfiltered, and even AC power applied to the plate (anode) electrodes. This rather relaxed regulation resulted from considering interference to broadcast stations. Most believed that key thumping, the transient production of harmonics by sharp on-off keying of a CW transmitter (later called key clicks) was the primary source of such interference. So even though using a pure DC supply resulted in a cleaner signal, special design was still required to eliminate thumping. The regulation also required that an antenna could not be directly coupled to a transmitter. Aside from increased efficiency, this would further limit interference from harmonics and power supply modulation.

In the 150 to 200 meter band the restrictions on transmission modes were relaxed to permit all types of amateur transmissions, including spark.

In what Warner called the “crème-de-la-crème” of the new regulations, no quiet hours would be required on the new bands because of what was assumed to be a much smaller chance of interference to broadcast listeners. Amateurs could once again transmit during the evening prime time.

Before amateurs could operate in the new bands, they had to return their licenses so that new ones permitting it could be issued. Access to some or all of the new allocations could be granted for each applicant on an individual basis. And all of this would be subject to change at the September conference. Amateurs were urged to get active on the new bands as soon as possible to build a case for continued access.

One month after the Commerce Department’s announcement, Canada granted the same bands to their amateurs but with two significant differences: They must use only pure CW, and loose coupled transmitters would not be required.6 They were tight on clean signals while being lax on harmonics.

![]()

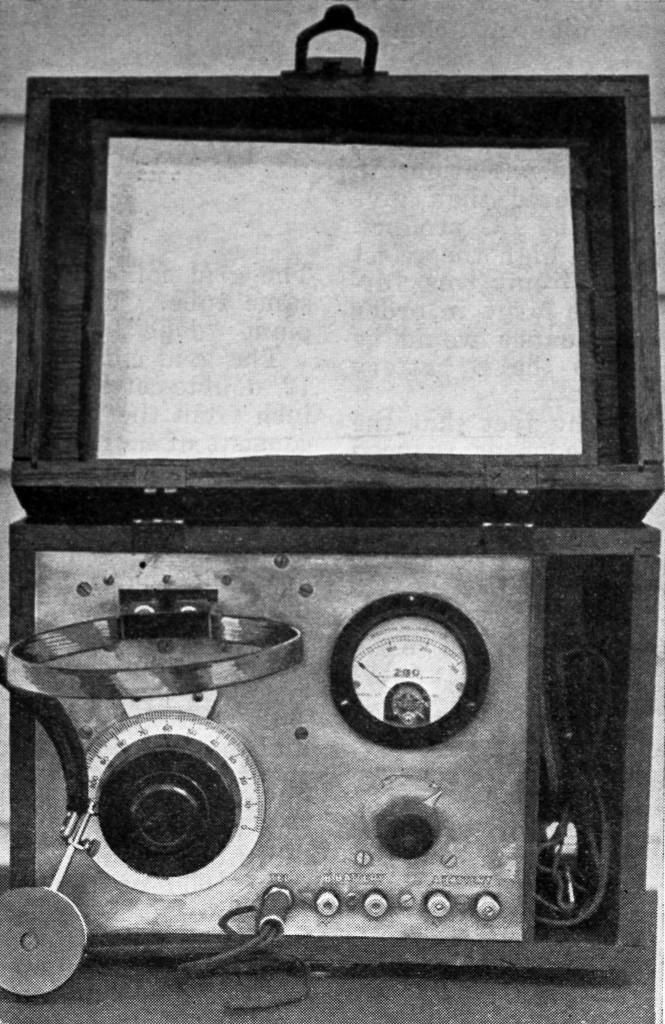

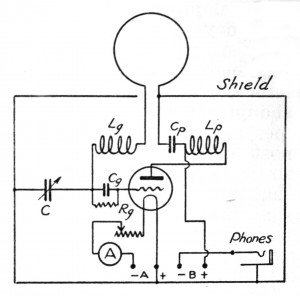

To prepare amateurs to occupy the new bands, QST Technical Editor Robert S. Kruse wrote about techniques and circuits to get them there.7 He began by loudly assuring everyone that “THERE IS NOTHING STRANGE ABOUT THE 20 to 100 METER REGION.” Wavelengths below 20 meters, however, required “special stunts” due to tube characteristics and so operation on the 4 to 5 meter band would be treated in a separate article. In any event, the first thing to do was to get a shortwave wavemeter. “It is absolute nonsense to start sending and receiving at 40 meters unless one knows where 40 meters is. Don’t do it. Just for once break all amateur traditions and make a wavemeter FIRST,” he pleaded.

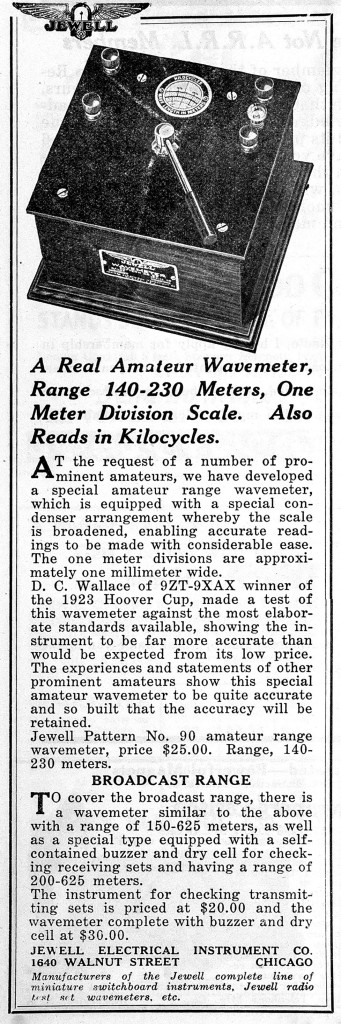

Recognizing a widespread lack of ability to measure wavelength, Kruse, also a Bureau of Standards engineer, had recently written a two-part article about wavemeters.8 They were already available commercially from General Radio and the Jewell Electrical Instrument Company, and were also not very difficult to build. A homemade wavemeter simply consisted of a calibrated tuned circuit and an indicator such as a crystal detector and headphones, light bulb, or galvanometer. One must choose a variable capacitor and inductor that would result in enough space on an adjustment dial to sufficiently resolve individual signals. They must also be built from mechanically well engineered and constructed parts. A flimsy variable capacitor would easily lose calibration. The quality of the tuning components was far more important than the indicator.

The best standard for calibration was the Bureau of Standards station WWV since other stations’ wavelengths were not particularly accurate. You could also set a wavemeter to another known calibrated wavemeter or send it to a lab for calibration. Calibration of a standard, commercially available numerical scale (tuning dial) could be done by plotting its settings on a graph.

Even with a calibrated wavemeter, using one to calibrate your equipment was a complicated process in 1924. When using the wavemeter with a transmitter, the coupling needed to be very loose or you’d risk burning out the indicator if it was a bulb. To use a wavemeter with a receiver, you would first set the receiver’s detector into oscillation. Next, with the wavemeter coil very close to the detector’s secondary circuit, you’d tune it until you heard a click in the receiver, indicating that the instrument was loading the receiver’s detector circuit and stopping its oscillations. Then, you would continue to tune in the same direction until you heard a second click, indicating you’d gone beyond the point where it again oscillated. Now you’d back off the distance to the wavemeter in steps until the two points converged; that would be the measurement point. The click method would work when receiving a signal too.

Homebrew wavemeter circa 1924

Kruse warned, however, against calibrating your receiver’s tuner since the markings will not have any meaning unless all the various settings were re-set exactly the same way each time, which, he matter-of-factly stated was impractical in most tuners and therefore “it is ‘the bunk’ to calibrate a tuner—keep a wavemeter handy instead.” With a calibrated receiver dial still a distant dream, Kruse’s advice was: don’t even try it!

He then presented circuits for use in receiving shortwaves and variations on the Hartley and Colpitts oscillators for transmitting, designs that would be in use for decades to come. Since it was important to control stray capacitances and resistances, Kruse recommended that, “sockets and tube bases should be removed—they have no business in a 20 meter set.” Tubes should be wired in without sockets!

Two years earlier, Kruse and Mason, QST’s Department Editor, had announced the formation of the ARRL Radio Information Service. Its purpose was to answer questions, mostly of a technical nature, submitted by League members.9 The service was needed, they wrote, because waiting for the next QST took too long and “the average amateur does not want to wait long for his information. He would rather ‘try it and see if anything blows up’.” The smoke test has a long tradition.

Example wavemeter circuit

Thus, the service endeavored to answer technical questions directly by exchanging letters with members, although the editors admitted that this “takes up most of the time of four people.” They asked members to help them by sending in new information of all sorts as they found it; in this way the service could act as a central repository. To prime the readership, they presented a list of information actively being sought, including experiences with Beverage wires and counterpoises, antenna insulators, “transmission as affected by the moon and the barometer,” tube comparisons, and information about “’dead spots’ you know of,” meaning skip zones.

The service’s rules were simple: check your back issues of QST before asking something that has already been covered there; supply a diagram and other full information so that a complete answer could be given; and since “all radio men write a terrible ‘paw’, use a typewriter.”

With the accelerating pace of changes and the announcement of new bands, the frontier where no ham had gone before, the Information Service was beginning to feel overwhelmed. The League reiterated its rules10 and added a final item: “Please remember, Rome was not built in a day.”11

![]()

The National Radio Conference had gone on record favoring the elimination of spark radio and the Commerce Department was expected to follow suit.12 The department would not recall licenses since the 1912 law, which was still in effect, allowed the possession of spark equipment and because it seemed unnecessary since fewer than one percent of ARRL members were still using spark. Warner did not believe that even a hundred of them were left.

The department asked for ARRL cooperation, prompting this response:

The A.R.R.L. here and now calls for the complete and immediate abolition of the amateur spark. Its day is done: let it begone. This is a civilized age and we have no place for decrement today. The editors of QST have owned and operated sparks that were their joy and pride, sparks as good as most of them, and nobody knows better than we the romance and fascination of the old rotary. But its name is Mud today and out it must go, 100%.

With that announcement spark would shortly disappear from the air forever.

![]()

On 6 October 1924, eighty representatives from every radio service and region of the country gathered for five days to attend Secretary Hoover’s third National Radio Conference.13 The conference recommended allocations that were nearly the same as those announced by the department in July and had been in use ever since. Its conclusions were termed “advisory” and would not become official until the Department of Commerce adopted them, which was expected to happen soon. As Warner wrote, “All the wavelengths from 0 to 3158 meters” were allocated for one year, anticipating annual conferences for continual review.

| Wavelength (meters) | Allocation |

| 0 – 4.7 | Beam transmission |

| 4.7 – 5.3 | Amateur |

| 5.3 – 16.7 | Beam transmission |

| 16.7 – 18.7 | Public service and mobile |

| 18.7 – 21.2 | Amateur |

| 21.2 – 25.8 | Public service |

| 25.8 – 27.3 | Relay broadcasting, exclusive |

| 27.3 – 30.0 | Public service |

| 30.0 – 33.3 | Relay broadcasting, exclusive |

| 33.3 – 37.5 | Public service and mobile |

| 37.5 – 42.8 | Amateur, and army mobile |

| 42.8 – 51.7 | Public service |

| 51.7 – 54.5 | Relay broadcasting, exclusive |

| 54.5 – 60.0 | Public service |

| 60.0 – 66.7 | Relay broadcasting, exclusive |

| 66.7 – 75.0 | Public service and mobile |

| 75.0 – 85.6 | Amateur, and army mobile |

| 85.6 – 103.3 | Public service |

| 103.3 – 109.2 | Relay broadcasting, exclusive |

| 109.2 – 120 | Mobile |

| 120 – 137 | Aircraft, exclusive |

| 137 – 150 | Point-to-point non-exclusive |

| 150 – 200 | Amateur |

| 200 – 545 | Phone broadcasting, exclusive |

Broadcasting was again the conference’s main concern. In addition to the previous vacating of 450 meters by marine users, 300 meters was freed up resulting in a continuous broadcasting band from 200 to 545 meters, adding thirty new channels. A committee was already in the process of assigning specific wavelengths to broadcast stations. It would proceed according to classes: Class 1, the best stations, 545 to 280 meters, Class 2, 275 to 214, Class 3, 211 to 205. Five channels were set aside specifically for small stations transmitting less than 100 watts. The displaced distress and marine users got five wavelengths above 600 meters along with the 1579- to 2500-meter band.

And in support of broadcasting networks yet to come, “It was believed that nationwide broadcasting by interconnection of stations deserved every encouragement and stimulation and to that end the Conference recommended the appointment of a continuing committee to work out necessary plans for its accomplishment.”

The amateur allocations were later changed slightly to make them harmonically related. This was done to avoid interference that might result from the generation of harmonics from an amateur band falling onto wavelengths assigned to other services. The same scheme was applied to the other services, too. This emphasis on managing harmonics was proposed by Dr. A. N. Goldsmith of the allocations committee, where the motto was “Everybody must eat his own mush.”

Maxim officially represented amateur radio on the important allocations committee, with ARRL secretary Kenneth Warner as alternate, and Vice President Charles Stewart as an additional advisor. Besides Maxim, the amateur sub-committee included Stewart, Warner, Professor C. M. Jansky of the University of Minnesota, Edwin Armstrong, and several other notable hams with professional ties to commercial radio. This committee recommended allowing the use of all amateur allocations under a single license, implicitly doing away with special licenses. To partly address interference concerns, they recommended that phone and ICW14 be allowed only on 170–180 meters, and that there be no provision for spark anywhere. They further recommended that loose transmitter coupling to the antenna be required to minimize harmonic generation, and that using receivers capable of also emitting signals should be discouraged.15 And as a matter of operating procedure, they endorsed the “confirmation” of the League’s system of intermediates16 for international identification.

Equally important as their direct participation on the allocations committee, the hams also had a friend in Secretary Hoover who specifically instructed the committee to take “adequate care of the amateurs.” Allocations were thus made in “an atmosphere in which the undoubted disapproval of certain commercial interests was necessarily subdued,” observed Warner. Hoover was so overtly appreciative of all that amateur radio had done and placed such emphasis on preserving it that “one might almost suppose that during his leisure moments he was a radio amateur himself,” wrote Electrical Engineering Professor A. E. Kennelley of Harvard.17

Kennelley highlighted two interesting characteristics of the new allocations: One was that the ratio of highest to lowest frequency in each band was 1.143, with the exception of the 150-200 meter band. Secondly, as Goldsmith had remarked at the conference, all the other new bands were even harmonics of that lowest frequency band. The same scheme applied to all radio services to ensure that harmonics always occurred within the bands of the same service that produced them. Kennelley’s more prosaic and wordy version of Goldsmith’s “mush” remark was, “As one member of the conference expressed the matter colloquially, each service should be charged with the duty of consuming its own harmonic excrescenses.”

He then reiterated the common understanding that waves of shorter length were more readily absorbed by land and sea than longer ones, proven by experiment. Long waves, therefore, should always have an advantage in long distance communications. Still, he admitted, it was a fact that 100-meter waves cross the oceans at night with very little power and no satisfactory explanation had yet been proven. He speculated that the answer might lie in the existence of an upper atmospheric conductive layer, as first suggested by scientists in 1902. If the transition from non-conducting to conducting was sharp enough, the absorption might be minimal, and perhaps favor the shorter waves. “This is only one of the many and debatable questions which today cannot be answered, but which the work of amateurs may be able to find an answer for in the future,” predicted Kennelley.

![]()

After the conference, a new bill was proposed directly by Secretary Hoover, again emphasizing broadcasting.18 In a letter addressed to Congressman White, Hoover said he believed that comprehensive legislation would ultimately be required but could not be rushed. Determining its shape would take time, probably another year. Meanwhile, he proposed a “short bill” to help manage things in the interim. This also would have the effect of sidelining the existing White bill.

Significantly, he envisioned that broadcasting might be considered a public service instead of, or in addition to, a commercial business. If so, whatever legislation emerged would be fundamentally different from previous laws. Setting this tone of public ownership, he wrote that, “the ether within the limits of the United States its territories and possessions is the inalienable possession of the people thereof, and that the authority to regulate its use in interstate and/or foreign commerce is conferred upon the Congress of the United States by the Federal Constitution.”

The proposed legislation would also modify the 1912 law to give the Secretary of Commerce the responsibility and power to regulate, at his “discretion,” the operation by licensees, including wavelengths, emission characteristics, and equipment—just as was provided in the White bill. Naturally, it therefore raised the same warning flags as before, both at the League and at the National Association of Broadcasters.

New regulations were put into effect starting on 25 January 1925 as a result of the convention.19 They included minor changes to the boundaries of the five amateur bands: 150 to 200 meters, 75 to 85.7 meters, 37.5 to 42.8 meters, 18.7 to 21.4 meters, and 4.69 to 5.35 meters. (Frequency specifications were on the way but hadn’t yet been widely adopted.) Spark should be abandoned “as soon as possible” but continued to be permitted in the 170 to 180 meter segment along with ICW. Strict requirements on equipment design included loose coupling to the antenna to reduce harmonics and other spurious effects, but there were still no requirements on power supplies—only that the emitted wave should be “sharply defined.” Quiet hours would only be observed above 150 meters wavelength as before. And all licensees would be granted access to all of the bands. Thus there was no further need for special licenses, and no new ones would be issued. Recognizing how strongly hams identities were tied to their call signs, current holders of the special “Z” calls would be allowed to keep them.

A few months later the commerce department announced a sixth new band of “ultra short waves” at ¾ meters for amateur reflection development or beam transmission20, both terms referring to directional radiation patterns. The band would be from 400 to 401 MHz. “Now we’re all set to try beam transmission at a frequency where the physical dimensions of the reflector apparatus will fit the average amateur’s static-room,” commented Warner. While the band would not see much actual use for more than a decade, the early willingness of Commerce to provide amateurs with yet another band indicated the value they placed on the exploratory work hams had been doing.

Band allocations, signal standards, regulatory authority—it was all there, to form a framework for the future evolution of radio for decades to come. But not before a major flaw in its foundation would threaten to bring it all crashing down.

![]()

de W2PA

- K. B. Warner, “The New White Bill,” Editorial, QST, May 1924, 7. ↩

- See also, Twenty-two in ‘22 ↩

- K. B. Warner, “The Radio Tax is Eliminated,” Editorial, QST, June 1924, 8. ↩

- These corresponded to 3.75 to 4.0, 6.25 to 7.5, 13.6 to 15, and 60 to 75 MHz. ↩

- “The New Short Waves,” Editorial, QST, September 1924, 7. ↩

- F. H. Schnell, “Canadian Amateurs Get Short Waves Too,” QST, October 1924, 12. ↩

- R. S. Kruse, “Working at 20, 40 and 80 Meters,” QST, September 1924, 9. ↩

- S. Kruse, “Amateur Wavemeters,” QST, February 1924, 22 and April 1924, 20. ↩

- S. Kruse, S., and H. F. Mason, “The League’s Radio Information Service,” QST, August 1923, 26. ↩

- “Easy on the Questions,” QST, September 1924, 26. ↩

- “Rules Governing the ARRL Information Service,” QST, December 1924, 33. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “Exit the Spark” (mislabeled “New Problems” in a page typesetting error), Editorial, QST, December 1924, 7. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “The Third National Radio Conference,” QST December 1924, 16. ↩

- Interrupted CW—a modulated CW signal using a “chopper” to pulse it to make it audible in a non-oscillating receiver. ↩

- C. B. Desoto, “Two Hundred Meters and Down,” The American Radio Relay League, Inc., 1936, 99. ↩

- See also “Call Sign Confusion.” ↩

- A. E. Kennelley, “The Conference in Relation to Amateur Activities,” QST, December 1924, 18. ↩

- “The Hoover Bill,” QST, February 1925, 7. ↩

- “New Regulations for Transmitting Stations,” QST, March 1925, 29. ↩

- K. B. Warner, “A New Amateur Band at 3/4 Meter,” QST, May 1925, 36. ↩