Finally, nearly one year after the armistice, a breakthrough: A single, tacked-on page, after the end cover of October QST, a hastily added special announcement proclaimed: “BAN OFF! THE JOB IS DONE AND THE A.R.R.L. DID IT. See next QST for details”

Finally, nearly one year after the armistice, a breakthrough: A single, tacked-on page, after the end cover of October QST, a hastily added special announcement proclaimed: “BAN OFF! THE JOB IS DONE AND THE A.R.R.L. DID IT. See next QST for details”

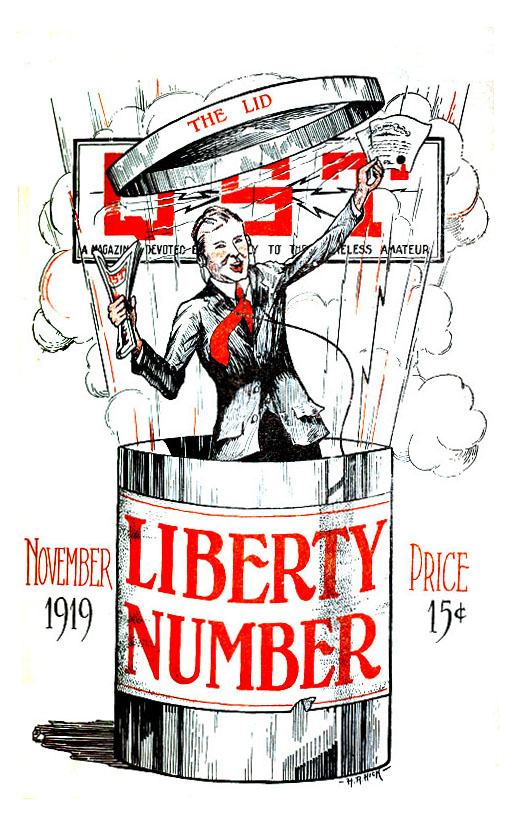

The HR Hick cover drawing for the November issue depicted a joyous ham bursting from the top of a can, popping off the lid (which, just to make sure the metaphor was understood, is labeled “the lid”)—he clutches a copy of QST in one hand, a certificate in the other. The can’s label reads “LIBERTY NUMBER” in big letters.

The issue opened with Maxim writing on the importance of organization, citing both the establishment of the League and radio clubs1 as prime examples. Only by having a national organization were hams able to influence the government on the one hand by preventing legislation that threatened amateur radio’s existence, and assist it on the other by providing wartime operators on very short notice. “It was a noble effort for all concerned, and lifted amateur radio from the realm of toyland to the dignity of a valuable National asset.” Aside from self preservation, another benefit of organization was to enable doing momentous things, such as the transcontinental relay work, impressive to outsiders. “Up to the time that we amateurs began relay work, the limit which one could transmit intelligence without paying tribute either to the Government or the Western Union or the Postal Telegraph Company, was the distance one’s voice would carry.”

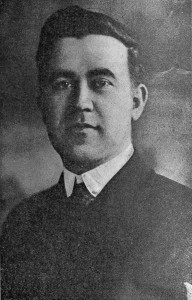

William S. Greene

Amateurs also had received help from friends in Congress. William Steadman Greene, the 78-year-old Chairman of the House Committee on The Merchant Marine and Fisheries, representative from Massachusetts, and “loyal protector of amateur rights,” was credited with the successful reopening.2 Greene had been the one who introduced the resolution, on the League’s behalf, asking the Navy to supply a reason for the continuing ban. Receiving no reply, he had then introduced Joint Resolution 217 directing the secretary of the Navy to remove the restrictions.

The League headquarters staff had to scramble to add the “ban off” insert to the previous issue when the news arrived just at press time.3 It would now take some hard work to get everything and everyone up and running again. “The days of real sport are at last with us,” noted ARRL secretary Kenneth Warner, directing readers to “Come on, fellows, and get into the air again.” An incredible array of new gear developed and manufactured during the war was becoming available, and that meant increased advertising revenue for QST—its life blood. The editor predicted a day when QST could be 132 pages long—twice the size of this issue. It would actually take until September of the following year for the magazine to again reach 100 pages, a size previously seen in April 1917, nearly three and a half years earlier.

Getting back on the air meant everyone had to be relicensed. Though some still had unexpired commercial licenses which the government would count as operator licenses, all amateur operator and station licenses had expired.4 As before the war, a Second Class license would be granted without examination to applicants located more than 50 miles from a district office. One could take a test given by the district inspector by appointment, and receive a First Class amateur license on successfully passing it. The new test format was a bit different, requiring longer answers from the applicant to demonstrate depth of understanding. The government published a document called “Radio Communication Laws of the United States,” containing the regulations one must know for the test.

On receiving an operator license you could next apply for a station license using a form to describe various aspects of your station. That information, and how well you had complied with the law in building it, determined whether or not the license would be granted. Radio Inspectors were authorized to disclose the call sign that an applicant would be issued once a station license was granted. The licensee would then be permitted to begin operation without waiting for the actual license to arrive in the mail. Hams were encouraged to send their new call signs to ARRL as they were issued so that they could be published and help everyone to once again recognize one another on the air.

The first directory of calls appeared in December, listing only new first district stations, apparently the only district reporting new licenses to that point. The list included the Harvard Wireless Club, 1AF, M.I.T., 1AN, Maxim, 1AW and Tuska, 1AY. Some stations in other districts had been given permission to use their old calls, possibly because they held unexpired commercial licenses. Some of these stations were prominent pre-war relayers, organizations, and operating department officers, including Mrs. Candler, 8NH, F. H. Schnell, 9AH, R. H. G. Mathews, 9ZN, J. O. Smith, 2ZL and Charles Service, 3QZ.

On the air, things were still very quiet even though the winter, the prime radio season, approached. The Atlantic Division manager reported hearing mostly silence on the first night of reopening, and only a few locals. Activity returned gradually as everyone worked to connect equipment and erect antennas. Licensed or not, amateurs had refrained from reassembling their stations before the reopening, perhaps due to uncertainty about when it would occur given the long delay, or perhaps because they stuck to the letter of the law that prohibited even assembling a station during the shutdown.

“In Memoriam” for December listed 11 more amateurs, some killed while serving in the military.

WCC on Cape Cod had a long history in a medium with a short one. Wired telegraph services such as the transatlantic cable were Marconi’s natural initial competition. In 1914 he established a station at Chatham, Mass., to replace his earlier one in Wellfleet. That one had made history in 1903 by relaying a message from President Theodore Roosevelt to the King of England directly via wireless using its 35-kW spark transmitter feeding a 200-wire conical antenna supported by four, 210-foot towers.5 WCC—originally simply “CC” for Cape Cod—became one of the most prominent wireless stations in the United States, and Irving Vermilya had been a station manager there since early 1916. Answering the Navy’s call for radio operators, he enlisted in 1917, served during the war, and then returned home to Massachusetts and WCC.

Irving Vermilya in 1920

He was back on the air and in print again in December 1919, publishing another QST humor article, “S.O.L.” (meaning “shit outta luck,” though not labeled as such in the article), telling of his early days in the Navy.6 By this time he had become well enough known among hams to be often identified by his last name alone. Everyone else in QST was referred to as Mr. so-and-so, or by their complete name—but “Amateur Number One” was just Vermilya. Everyone finally got a look at him in the February 1920 issue’s installment of Who’s Who in Wireless,7 identified as a shift engineer at the Marconi station. The article paraphrased him as admitting that “he’d rather fuss with wireless than eat, and his record shows it.”

In October, pictures of his station appeared too—he was now 1HAA, “a good call for a funny man”—in Marion, Massachusetts.8 His antenna was a fan array of vertical wires, narrow spaced at the base and wide at the top, connected to a horizontal wire suspended between wooden supports, very similar to Maxim’s antenna and considered a leading-edge design. Two interior pictures depict a neatly arranged, high-power spark station. Another change in call sign came in July 1921, when he received a special station license and QST announced that “1HAA is no more. Vermilya is now 1ZE, using 200, 250, and 375 meters.”

He continued to work for United Wireless after its acquisition by Marconi, working as manager of WCC until he left the Radio Corporation in 1922 to become manager of the radio department at Slocum & Kilburn, a parts and equipment company.

Vermilya would continue to play a role in two camps—as professional and amateur.

de W2PA

- Hiram Percy Maxim, “The Importance of Our ARRL,” QST, November 1919, 3. ↩

- “The Champion of the Amateurs,” QST, November 1919, 5. ↩

- “At Last!,” Editorial, QST, November 1919, 13. ↩

- “Getting Your Licenses,“ QST, November 1919, 12. ↩

- “In Search of Guglielmo,” ARRL Web, 17 Mar 2005 ↩

- Although it was billed as the first of a two-part article, the second part never appeared. ↩

- Who’s Who in Amateur Wireless, QST, February 1920, 25. ↩

- Amateur Radio Stations, QST, October, 1920, 35. ↩